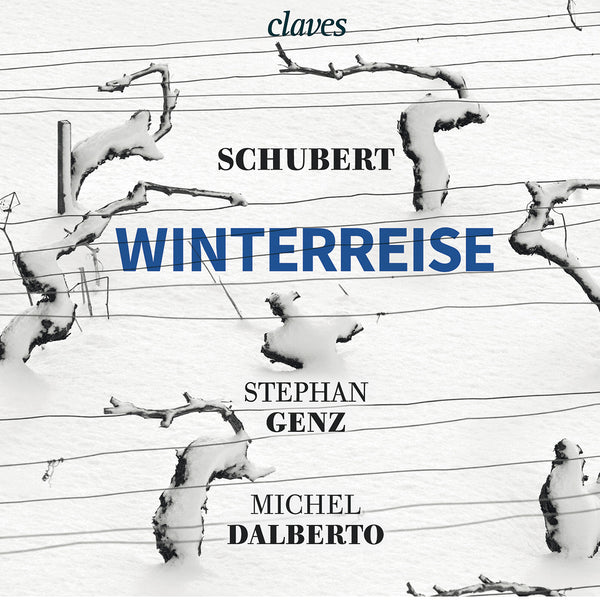

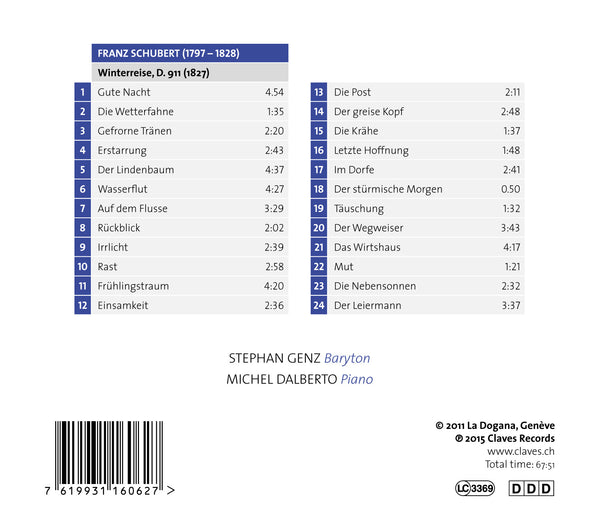

(2015) Schubert : Winterreise D 911 - Stephan Genz, Michel Dalberto

Catégorie(s): Chant lyrique Piano

Instrument(s): Piano

Voix: Baryton

Compositeur principal: Franz Schubert

Nb CD(s): 1

N° de catalogue:

CD 1606

Sortie: 10.10.2015

EAN/UPC: 7619931160627

- UPC: 191018814878

Cet album est en repressage. Précommandez-le dès maintenant à un prix spécial.

CHF 18.50

Cet album n'est pas encore sorti. Précommandez-le dès maintenant.

CHF 18.50

CHF 18.50

TVA incluse pour la Suisse et l'UE

Frais de port offerts

TVA incluse pour la Suisse et l'UE

Frais de port offerts

Cet album est en repressage. Précommandez-le dès maintenant à un prix spécial.

CHF 18.50

This album has not been released yet.

Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

CHF 18.50

SCHUBERT : WINTERREISE D 911 - STEPHAN GENZ, MICHEL DALBERTO

Schubert had already set Wilhelm Müller’s poetic cycle “Die schöne Müllerin” in 1823, and at some point he came across twelve new poems by Müller entitled “Wanderlieder … Die Winterreise” that had been published in the Urania almanac in Leipzig. He set them to music in early 1827. Not long afterwards, Schubert discovered that Müller had meanwhile added another twelve poems to form a larger cycle, publishing them collectively as “Die Winterreise” in a volume called “Poems from the posthumous papers of a travelling horn player”. In order to give his cycle more of a coherent narrative, Müller had juggled the order of his original twelve, mixing some of the new poems among them. But Schubert decided to leave his first twelve songs as they were, and in the late summer of 1827 simply set the new twelve poems to music in the order in which they appeared in Müller’s expanded cycle (the exceptions being “Mut” and “Die Nebensonnen”, which he swapped around). Schubert’s first group of twelve Winterreise songs was published by Haslinger in Vienna in early 1828. The proofs of the second dozen did not arrive until the late autumn. Schubert corrected them when he was already on his deathbed, and by the time the songs were published in December 1828, its composer had been dead for a month.

There is a narrator in the Winterreise, but not much of a narrative. Rejected by the woman he loves, the wanderer leaves home at night. He wanders past haphazard reminders of his lost love – the house where she lived, the linden tree into whose bark he’d carved his sweet nothings, the meadow where once they’d strolled together, then a post coach that he hopes might carry word from her (but doesn’t). A crow circles above as he wanders on. Dogs bark angrily as he crosses a village, he finds himself in a cemetery, and at the end he goes off with a barefoot hurdy-gurdy man who might or might not be real, but in any case represents death. Yet apart from the beginning and the end, there is little that is linear about any of this – not least because of Schubert’s refusal to bend to the final order of Müller’s cycle. Instead, Schubert offers us a depiction of a fractured, spiralling consciousness in which present, past and future intermingle. The wintry weather offers its signifiers of decay and dying throughout – the frozen tears, the falling leaves, the fir trees bent to the wind, the snow blowing in the wanderer’s face and his hair turned white from frost. The environment, both natural and emotional, is more important here than any story.