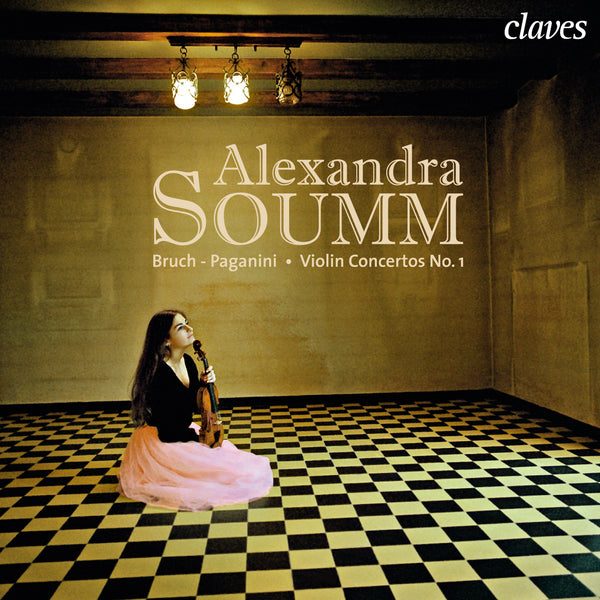

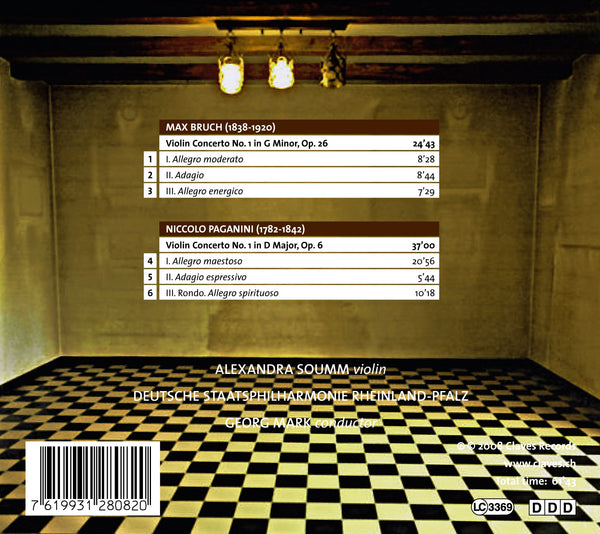

(2008) Bruch: Violin Concerto No. 1 - Paganini: Violin Concerto No. 1

Catégorie(s): Concerto Début

Instrument(s): Violon

Compositeur principal: Niccolò Paganini

Orchestre: Deutsche Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz

Chef: Georg Mark

Nb CD(s): 1

N° de catalogue:

CD 2808

Sortie: 2008

EAN/UPC: 7619931280820

- UPC: 884385198701

Cet album est en repressage. Précommandez-le dès maintenant à un prix spécial.

CHF 18.50

Cet album n'est plus disponible en CD.

Cet album n'est pas encore sorti. Précommandez-le dès maintenant.

CHF 18.50

Cet album n'est plus disponible en CD.

CHF 18.50

TVA incluse pour la Suisse et l'UE

Frais de port offerts

Cet album n'est plus disponible en CD.

TVA incluse pour la Suisse et l'UE

Frais de port offerts

Cet album est en repressage. Précommandez-le dès maintenant à un prix spécial.

CHF 18.50

Cet album n'est plus disponible en CD.

This album has not been released yet.

Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

Cet album n'est plus disponible en CD.

CHF 18.50

Cet album n'est plus disponible en CD.

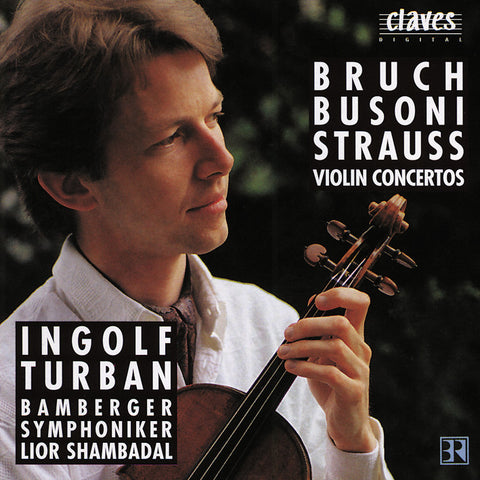

BRUCH: VIOLIN CONCERTO NO. 1 - PAGANINI: VIOLIN CONCERTO NO. 1

Passion and Poetry

But if one transcends such clichés two constants become evident: his works are not actually inordinately more difficult than others; they are in fact certain to be in the repertoire of every violinist of any talent; and passion and poetry are not foreign to his music. Paganini’s First Violin Concerto is marked by great skill in the measured use of effects; effects employed equally for expression as for bravura. In the original version; the use of scordatura is a good point in case: faced with an orchestral score in E-flat major; he wrote the solo violin part in D major; obliging the soloist to tune a half-tone higher.

The benefits are double: the sonority of the violin is clearer and the difficulties for the left hand are reduced in certain virtuoso passages. Written in three classical movements; the lyrical work much in the style of Rossini’s bel canto is sprinkled with chains of dazzling chords; harmonies or other “eccentricities”. The accompaniment is discrete; encasing and displaying the solo voice without; however; being deprived of warmth or a sense of drama.

Twelve Attempts

When listening to the definitive version of Max Bruch’s First Violin Concerto; one has the impression it was written in one stroke. In reality; however; the composer suffered great doubts during work on the composition from 1864 to 1868; he made no less than twelve attempts before creating the final manuscript. His correspondence with the great violinist Joseph Joachim gives detailed witness to his efforts.

The future dedicatee of the work; Joachim made significant contributions to the incomparable writing of the solo part. He filled the same sort of role a dozen or so years later with Johannes Brahms when the latter embarked on his violin concerto.

Fantasy

Bruch; like Brahms; refused to “yield to the errors of modern composers”; but he nonetheless adopted a rather unconventional structure for his concerto; which he had initially entitled Fantasy. During the course of the Prelude the soloist states three principal thematic motives that are developed over successive cadenzas and lead up to the inspiring Adagio. In the Adagio the spirit of an expressive melody unfolds in the true art of Romantic composition; leaving the sparkling virtuosity to the final Allegro energico.

“Formally Forbidden”

Bruch’s Opus 26 immediately became one of the most frequently performed violin concertos. But the rewards of this success brought a shadow that plagued the composer: would his other compositions; his three operas; a symphony; the chamber music and his chorale works remain doomed to neglect?

But an ironic stroke of fate came to his aid; a fictional decree that publicly announced: “since for some time one has observed the remarkable fact that violins perform this First Concerto by themselves; we would like to announce that this work has been formally forbidden for the moment in order to appease anxious souls.” It is certainly unfortunate that his concerto cast a shadow over his other works; but Bruch’s popularity has remained nonetheless intact.

Benjamin Ilschner

(Translation: Mark Manion)

“Paganini. Never tuned his violin. – Famous for the length of his fingers.” This is the entry in Gustave Flaubert’s Dictionnaire des idées reçues [dictionary of received ideas]; published posthumously in 1911. It is an extreme form of a frequent caricature; as the legend according to which the violinist from Genoa concluded a pact with the devil in order to achieve dazzling feats of virtuosity. Or that at the peak of his career he felt absolutely no compassion for the technical limitations of his ordinary colleagues! The extravagant Niccolò Paganini performed throughout Europe; often appropriating the most alluring melodies without hesitation. The anecdotes about his compositions are countless; compositions often labeled as extremely difficult and flamboyant rather than lyrical and emotional.

Passion and Poetry

But if one transcends such clichés two constants become evident: his works are not actually inordinately more difficult than others; they are in fact certain to be in the repertoire of every violinist of any talent; and passion and poetry are not foreign to his music. Paganini’s First Violin Concerto is marked by great skill in the measured use of effects; effects employed equally for expression as for bravura. In the original version; the use of scordatura is a good point in case: faced with an orchestral score in E-flat major; he wrote the solo violin part in D major; obliging the soloist to tune a half-tone higher.

The benefits are double: the sonority of the violin is clearer and the difficulties for the left hand are reduced in certain virtuoso passages. Written in three classical movements; the lyrical work much in the style of Rossini’s bel canto is sprinkled with chains of dazzling chords; harmonies or other “eccentricities”. The accompaniment is discrete; encasing and displaying the solo voice without; however; being deprived of warmth or a sense of drama.

Twelve Attempts

When listening to the definitive version of Max Bruch’s First Violin Concerto; one has the impression it was written in one stroke. In reality; however; the composer suffered great doubts during work on the composition from 1864 to 1868; he made no less than twelve attempts before creating the final manuscript. His correspondence with the great violinist Joseph Joachim gives detailed witness to his efforts.

The future dedicatee of the work; Joachim made significant contributions to the incomparable writing of the solo part. He filled the same sort of role a dozen or so years later with Johannes Brahms when the latter embarked on his violin concerto.

Fantasy

Bruch; like Brahms; refused to “yield to the errors of modern composers”; but he nonetheless adopted a rather unconventional structure for his concerto; which he had initially entitled Fantasy. During the course of the Prelude the soloist states three principal thematic motives that are developed over successive cadenzas and lead up to the inspiring Adagio. In the Adagio the spirit of an expressive melody unfolds in the true art of Romantic composition; leaving the sparkling virtuosity to the final Allegro energico.

“Formally Forbidden”

Bruch’s Opus 26 immediately became one of the most frequently performed violin concertos. But the rewards of this success brought a shadow that plagued the composer: would his other compositions; his three operas; a symphony; the chamber music and his chorale works remain doomed to neglect?

But an ironic stroke of fate came to his aid; a fictional decree that publicly announced: “since for some time one has observed the remarkable fact that violins perform this First Concerto by themselves; we would like to announce that this work has been formally forbidden for the moment in order to appease anxious souls.” It is certainly unfortunate that his concerto cast a shadow over his other works; but Bruch’s popularity has remained nonetheless intact.

Benjamin Ilschner

(Translation: Mark Manion)

Return to the album | Composer(s): Niccolò Paganini | Main Artist: Alexandra Soumm

Albums populaires

Alexandra Soumm - violin

Claves picks

Concerto

Deutsche Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz

Diapason d'argent

Début

En stock

Georg Mark

Max Bruch (1838-1920)

Niccolò Paganini

Pizzicato.lu - Supersonic

Releases 2006 - 2008

Sommets musicaux de Gstaad (SMG)

Tous les albums

Violon

Albums populaires

Alexandra Soumm - violin

Claves picks

Concerto

Deutsche Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz

Diapason d'argent

Début

En stock

Georg Mark

Max Bruch (1838-1920)

Niccolò Paganini

Pizzicato.lu - Supersonic

Releases 2006 - 2008

Sommets musicaux de Gstaad (SMG)

Tous les albums

Violon