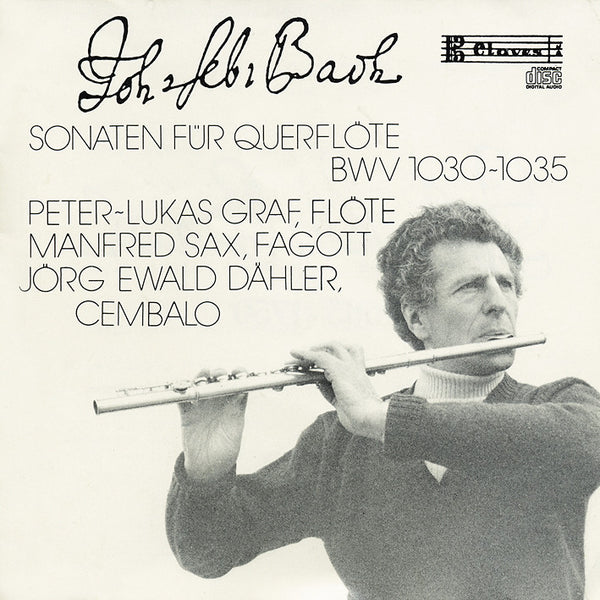

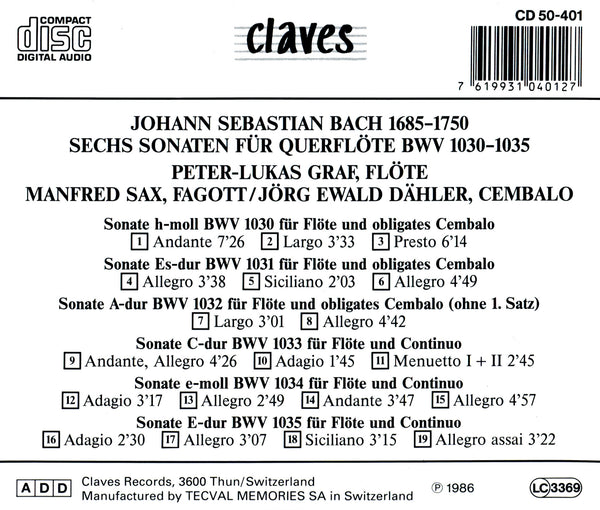

(1986) Bach: Sonatas for Flute BWV 1030-1035

Catégorie(s): Musique ancienne

Instrument(s): Basson Flûte Clavecin

Compositeur principal: Johann Sebastian Bach

Nb CD(s): 1

N° de catalogue:

CD 0401

Sortie: 1986

EAN/UPC: 7619931040127

- UPC: 829410603461

Cet album est en repressage. Précommandez-le dès maintenant à un prix spécial.

CHF 18.50

Cet album n'est plus disponible en CD.

Cet album n'est pas encore sorti. Précommandez-le dès maintenant.

CHF 18.50

Cet album n'est plus disponible en CD.

Cet album n'est plus disponible en CD.

TVA incluse pour la Suisse et l'UE

Frais de port offerts

Cet album est en repressage. Précommandez-le dès maintenant à un prix spécial.

CHF 18.50

Cet album n'est plus disponible en CD.

This album has not been released yet.

Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

Cet album n'est plus disponible en CD.

Cet album n'est plus disponible en CD.

BACH: SONATAS FOR FLUTE BWV 1030-1035

Parmi les sonates pour flûte allemande attribuées à Bach, seules cinq peuvent être considérées à juste titre comme des œuvres authentiques de celui qui était alors chef d'orchestre à la cour de Köthen (vers 1720). Sur le plan formel, ces sonates se distinguent par leur degré de parenté avec la « sonata da chiesa » en quatre mouvements, avec le type de sonate plus tardif en trois mouvements et avec la « sonata da camera », composée de plusieurs mouvements, qui s'apparente à la suite.

La sonate en do majeur et celle en si bémol mineur ne sont pas faciles à classer dans cette catégorie. Dans le premier mouvement de la sonate en do majeur, un lent prélude est suivi d'une magistrale fantaisie, la mélodie planant pour ainsi dire au-dessus d'une note de pédale ; dans le Menuet I, une partie de basse chiffrée devient une partie de clavecin écrite. De plus, la qualité « galante » de ce menuet s'écarte de l'expressivité tardo-baroque de l'adagio en la mineur.

La sonate en si bémol mineur, beaucoup plus pensive, se distingue des autres sonates de l'époque par la longueur du premier mouvement et ses tensions chromatiques, ainsi que par la combinaison d'un presto fugué et d'une gigue allegro dans le dernier mouvement. Sa valeur artistique - immédiatement apparente - se retrouve dans presque tous les aspects de la composition.

Dans sa sonate en mi mineur, Bach s'en tient strictement au style de la « sonata da chiese ». Il convient de mentionner la façon dont, dans le premier mouvement, le continuo reprend à plusieurs reprises le « cantabile » de la flûte, ainsi que la liberté avec laquelle Bach utilise la partie de basse (la traitant comme une voix soliste, obtenant ainsi un effet semblable à celui d'une chaconne). Le dernier mouvement, avec ses deux thèmes, présente un intérêt similaire.

La source de la sonate en mi bémol majeur est une copie datant du milieu du XVIIIe siècle, dont le titre est écrit de la main de Philipp Emanuel Bach. La conclusion selon laquelle un homme plus jeune que Bach pourrait être le compositeur de cette sonate est confirmée par le fait que le clavecin, dans le premier mouvement, adhère à des motifs qui lui sont propres et qui forment un contraste vivant avec les thèmes de la voix de flûte, ainsi que par l'humeur sensible et la touche pastorale de la sicilienne, et la fréquence des tierces parallèles dans le troisième mouvement.

Dans les quatre mouvements de la sonate en mi majeur, nous rencontrons Bach en tant qu'inventeur de mélodies harmonieuses ; un « cantilene » expressif et fluide caractérise le premier mouvement, de même qu'un « ductus » galant et mélodieux dans la forme sicilienne. Dans les deux mouvements rapides, Bach réalise les idées mélodiques qui deviendront la norme dans la musique classique ultérieure.

La sonate en la majeur, dans laquelle est composée la partie de basse, est particulièrement intéressante en raison de son harmonie à trois voix. Non seulement elle soutient, comme à l'accoutumée, toutes les autres parties, mais - surtout dans le mouvement lent - elle est d'une qualité mélodique remarquable. Le premier mouvement incomplet, difficile à reconstituer de manière satisfaisante, a été omis dans le présent enregistrement.

Quelques notes sur les interprétations de ce disque : Dans les compositions baroques comportant une partie de basse continue chiffrée, les interprètes sont libres de choisir leur propre instrument de basse. Le plus souvent, ils choisissaient, et choisissent encore, la basse-viol. Pour cet enregistrement, c'est un basson qui a été choisi - une idée qui présente l'avantage supplémentaire d'opposer distinctement le contrepoint à deux voix à la flûte, et de faire clairement contraster le clavecin avec les deux instruments à vent.

Il est vrai qu'il était parfois d'usage, comme dans les sonates, que le clavecin amplifie la voix de basse, mais cette coutume a été abandonnée au motif que dans une composition à trois voix (c'est-à-dire deux voix descendantes équivalentes jouées par la flûte et la main droite du claveciniste, plus une voix de basse placée par la main gauche du claveciniste), il n'y avait pas lieu d'en faire usage.

Pour cet enregistrement, seuls des instruments modernes ont été utilisés - mais le claveciniste tient compte du fait que Bach n'avait pas de pédales mécaniques par la manière dont il utilise ses jeux. Le changement de registre au cours d'une même œuvre n'était donc possible à l'époque baroque que dans la mesure du possible, avec les quelques jeux disponibles à l'époque.

Traduit de l'Anglais avec www.DeepL.com/Translator

(1986) Bach: Sonatas for Flute BWV 1030-1035 - CD 0401

Parmi les sonates pour flûte allemande attribuées à Bach, seules cinq peuvent être considérées à juste titre comme des œuvres authentiques de celui qui était alors chef d'orchestre à la cour de Köthen (vers 1720). Sur le plan formel, ces sonates se distinguent par leur degré de parenté avec la « sonata da chiesa » en quatre mouvements, avec le type de sonate plus tardif en trois mouvements et avec la « sonata da camera », composée de plusieurs mouvements, qui s'apparente à la suite.

La sonate en do majeur et celle en si bémol mineur ne sont pas faciles à classer dans cette catégorie. Dans le premier mouvement de la sonate en do majeur, un lent prélude est suivi d'une magistrale fantaisie, la mélodie planant pour ainsi dire au-dessus d'une note de pédale ; dans le Menuet I, une partie de basse chiffrée devient une partie de clavecin écrite. De plus, la qualité « galante » de ce menuet s'écarte de l'expressivité tardo-baroque de l'adagio en la mineur.

La sonate en si bémol mineur, beaucoup plus pensive, se distingue des autres sonates de l'époque par la longueur du premier mouvement et ses tensions chromatiques, ainsi que par la combinaison d'un presto fugué et d'une gigue allegro dans le dernier mouvement. Sa valeur artistique - immédiatement apparente - se retrouve dans presque tous les aspects de la composition.

Dans sa sonate en mi mineur, Bach s'en tient strictement au style de la « sonata da chiese ». Il convient de mentionner la façon dont, dans le premier mouvement, le continuo reprend à plusieurs reprises le « cantabile » de la flûte, ainsi que la liberté avec laquelle Bach utilise la partie de basse (la traitant comme une voix soliste, obtenant ainsi un effet semblable à celui d'une chaconne). Le dernier mouvement, avec ses deux thèmes, présente un intérêt similaire.

La source de la sonate en mi bémol majeur est une copie datant du milieu du XVIIIe siècle, dont le titre est écrit de la main de Philipp Emanuel Bach. La conclusion selon laquelle un homme plus jeune que Bach pourrait être le compositeur de cette sonate est confirmée par le fait que le clavecin, dans le premier mouvement, adhère à des motifs qui lui sont propres et qui forment un contraste vivant avec les thèmes de la voix de flûte, ainsi que par l'humeur sensible et la touche pastorale de la sicilienne, et la fréquence des tierces parallèles dans le troisième mouvement.

Dans les quatre mouvements de la sonate en mi majeur, nous rencontrons Bach en tant qu'inventeur de mélodies harmonieuses ; un « cantilene » expressif et fluide caractérise le premier mouvement, de même qu'un « ductus » galant et mélodieux dans la forme sicilienne. Dans les deux mouvements rapides, Bach réalise les idées mélodiques qui deviendront la norme dans la musique classique ultérieure.

La sonate en la majeur, dans laquelle est composée la partie de basse, est particulièrement intéressante en raison de son harmonie à trois voix. Non seulement elle soutient, comme à l'accoutumée, toutes les autres parties, mais - surtout dans le mouvement lent - elle est d'une qualité mélodique remarquable. Le premier mouvement incomplet, difficile à reconstituer de manière satisfaisante, a été omis dans le présent enregistrement.

Quelques notes sur les interprétations de ce disque : Dans les compositions baroques comportant une partie de basse continue chiffrée, les interprètes sont libres de choisir leur propre instrument de basse. Le plus souvent, ils choisissaient, et choisissent encore, la basse-viol. Pour cet enregistrement, c'est un basson qui a été choisi - une idée qui présente l'avantage supplémentaire d'opposer distinctement le contrepoint à deux voix à la flûte, et de faire clairement contraster le clavecin avec les deux instruments à vent.

Il est vrai qu'il était parfois d'usage, comme dans les sonates, que le clavecin amplifie la voix de basse, mais cette coutume a été abandonnée au motif que dans une composition à trois voix (c'est-à-dire deux voix descendantes équivalentes jouées par la flûte et la main droite du claveciniste, plus une voix de basse placée par la main gauche du claveciniste), il n'y avait pas lieu d'en faire usage.

Pour cet enregistrement, seuls des instruments modernes ont été utilisés - mais le claveciniste tient compte du fait que Bach n'avait pas de pédales mécaniques par la manière dont il utilise ses jeux. Le changement de registre au cours d'une même œuvre n'était donc possible à l'époque baroque que dans la mesure du possible, avec les quelques jeux disponibles à l'époque.

Traduit de l'Anglais avec www.DeepL.com/Translator

Return to the album | Read the booklet | Composer(s): Johann Sebastian Bach | Main Artist: Peter-Lukas Graf