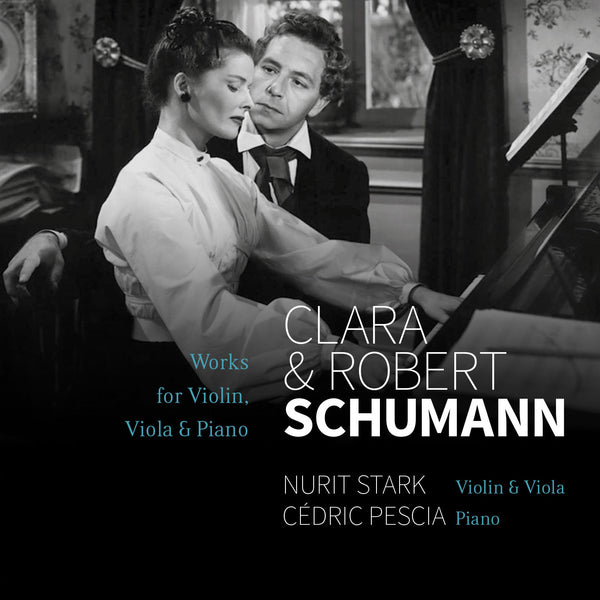

(2015) R. & C. Schumann: Works for Violin/Viola & Piano-N. Stark, C. Pescia

Catégorie(s): Piano

Instrument(s): Piano Alto Violon

Compositeur principal: Robert Schumann

Nb CD(s): 1

N° de catalogue:

CD 1502

Sortie: 01.01.2015

EAN/UPC: 7619931150222

- UPC: 191018908140

Cet album est en repressage. Précommandez-le dès maintenant à un prix spécial.

CHF 18.50

Cet album n'est plus disponible en CD.

Cet album n'est pas encore sorti. Précommandez-le dès maintenant.

CHF 18.50

Cet album n'est plus disponible en CD.

CHF 18.50

TVA incluse pour la Suisse et l'UE

Frais de port offerts

Cet album n'est plus disponible en CD.

TVA incluse pour la Suisse et l'UE

Frais de port offerts

Cet album est en repressage. Précommandez-le dès maintenant à un prix spécial.

CHF 18.50

Cet album n'est plus disponible en CD.

This album has not been released yet.

Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

Cet album n'est plus disponible en CD.

CHF 18.50

Cet album n'est plus disponible en CD.

R. & C. SCHUMANN: WORKS FOR VIOLIN/VIOLA & PIANO-N. STARK, C. PESCIA

Robert Schumann has also long been regarded as having lost his inspiration towards the end, more precisely after his move to Düsseldorf in 1850 to take up the post of music director. But his chances at wholesale rehabilitation are probably illusory. For while Beethoven was deaf, not dotty, Schumann’s state of mind in the early 1850s was often precarious. There were his séance obsessions, the voices in his head, the black dog days and finally the plunge into the Rhine after trying to pay the bridge-keeper’s toll with a handkerchief. Schumann’s wife Clara felt so embarrassed by his last works that she destroyed some and left others unpublished. But critics and commentators soon began reading Schumann’s madness much further backwards, taking earlier signs of formal irregularity in his music as proof of incipient insanity.

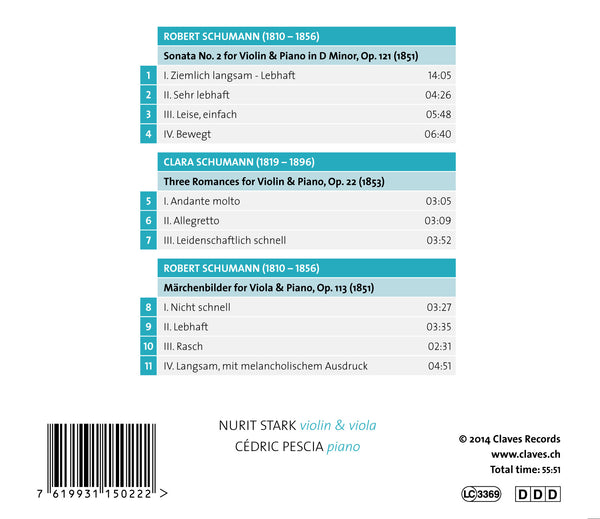

Schumann’s late works deserve a more differentiated approach. While we must acknowledge that several written before his final breakdown are hardly strong enough to catch on – such as the Violin Concerto – there are many others from his Düsseldorf years that are truly compelling. This latter group must include the works on this CD; the Märchenbilder (“Fairy tale pictures”) op. 113 and the Second Violin Sonata op. 121, both composed in 1851.

Schumann had begun his career as a composer for the piano, then after his marriage branched out successively into the lied, the symphony, chamber music, choral music and opera, almost as if he were ticking off one genre after another. His approach to chamber music for strings with piano was similarly methodical, though reductive: a piano quintet was followed by a piano quartet, then piano trios, and then from 1 to 4 March 1851 he wrote his first piano and string duo: the Märchenbilder for viola and piano (also issued with an alternative violin solo part). He dedicated them to Wilhelm von Wasielewski, his concertmaster in Düsseldorf, who tried them out with Clara and two years later gave their first public performance. Schumann called these pieces mere “childish pranks” though this was probably just overcautious modesty. Not only was this his first solo work for viola, but also just about the first-ever solo viola work by any Romantic composer of note. Schumann initially couldn’t decide on a title, calling them “viola stories”, “fairy-tale songs” and finally “fairy-tale pictures”, though all of these refer to the narrative element inherent in them. The first and third pieces certainly seem to be “telling” us something, though we know not what; the second is a “hunting horn” rondo; and the fourth and last piece sounds like a Brahmsian lullaby avant la lettre (its main theme, incidentally, seems to hover behind the opening of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony, also in D).

Schumann wrote his First Violin Sonata, op 105 in a minor, in September 1851. Barely a month later he was writing a Second, this time in d minor. Where the First was in three movements, the Second is cast in four and is altogether more expansive. The slow opening is in a sarabande rhythm and reminiscent of the Chaconne from Bach’s Violin Partita in d minor (a work that Schumann knew well). The opening theme is generally agreed to be based on the surname of the dedicatee, the violinist Ferdinand David (with an “f” substituting for his “v”). The same theme opens the fast-paced movement proper, which is by turns passionate and lyrical, hesitant and agitated and veritably sweeps one along. The second movement, in b minor, is a “hunting” scherzo whose shift into the major towards the close is a magical moment that just about every critic agrees is Schumann at his best. The third movement is a set of variations in G major on a theme – first given pizzicato by the violin – that is a simple as it is memorable (some, incidentally, hear in it an echo of Luther’s chorale “I cry to thee in deepest need”). The last movement is in sonata form, and in its tempestuousness recalls the first movement. Schumann had published his First Sonata soon after its composition, so it was probably just the fear that he might swamp the market that made him hold back the Second for another two years. Despite the dedication to David, it was Joseph Joachim who gave the work’s first public performance in autumn 1853, organized roughly to coincide with its publication. Joachim loved it, writing to his friend Arnold Wehner on 10 September that “it is for me one of the loveliest creations of recent times in its magnificent unity and the concision of its themes. It is full of passion … The last movement is splendid in the way it ebbs and flows, and could be a landscape of the soul”. But just a few months after the composer’s death, Eduard Hanslick was already damning the Second Sonata as proof of Schumann’s declining powers. It suited Hanslick’s historical view of things to see a long, gradual decline instead of any abrupt biographical fracture. But the work itself merits no such nonsense. Had Schumann suddenly died in 1852 instead of dwindling away afterwards, Hanslick might well have joined Joachim in declaring the work “magnificent”; for that’s what it is.

Clara Schumann’s great fortune in life – as she saw it – was to fall in love and marry a composing genius. Her great misfortune in life – one might argue – was the same. Fêted as one of the leading pianists of her age, she was also a gifted composer, though outshone by her husband. Robert was outwardly supportive of her composing efforts, but since Clara also functioned as the conveyor belt for his babies he was of little concrete help to her career – she produced almost as many children as she did opus numbers during their marriage.

Clara’s Three Romances for violin and piano op. 22 were composed in July 1853 and dedicated to Joachim. They belong among her “last” works – after this year, she hardly ever composed again. In stylistic terms they are clearly situated in the Mendelssohnian/Schumannian tradition. But even where their mood might seem at first to reflect the bourgeois salon, phrases here and there are subtly elongated or shortened, little cross-rhythms come and go (as in the opening bars of No. 1) and unexpected harmonies intrude (such as the augmented chords in the final bars of No. 3) that altogether reveal a more complex sensibility. After Robert’s decline, Clara returned to her career as a piano virtuoso in order to feed the family. A pity she did not resume composing on a larger scale; the music world would have been the richer for it.

Chris Walton

There are two common perceptions of “late works”, and they are mutually exclusive. The one regards “lateness” as a summation – a cumulative phenomenon in which the artist creates the crowning works of his oeuvre. The other sees lateness as decay. Some artists have been subject to both approaches. Beethoven’s last quartets were thought an embarrassing testimony to mental decline until Richard Wagner saw genius and logic in them where others had seen mere unreason. He declared them to be Beethoven’s masterpieces, and no one has disagreed since.

Robert Schumann has also long been regarded as having lost his inspiration towards the end, more precisely after his move to Düsseldorf in 1850 to take up the post of music director. But his chances at wholesale rehabilitation are probably illusory. For while Beethoven was deaf, not dotty, Schumann’s state of mind in the early 1850s was often precarious. There were his séance obsessions, the voices in his head, the black dog days and finally the plunge into the Rhine after trying to pay the bridge-keeper’s toll with a handkerchief. Schumann’s wife Clara felt so embarrassed by his last works that she destroyed some and left others unpublished. But critics and commentators soon began reading Schumann’s madness much further backwards, taking earlier signs of formal irregularity in his music as proof of incipient insanity.

Schumann’s late works deserve a more differentiated approach. While we must acknowledge that several written before his final breakdown are hardly strong enough to catch on – such as the Violin Concerto – there are many others from his Düsseldorf years that are truly compelling. This latter group must include the works on this CD; the Märchenbilder (“Fairy tale pictures”) op. 113 and the Second Violin Sonata op. 121, both composed in 1851.

Schumann had begun his career as a composer for the piano, then after his marriage branched out successively into the lied, the symphony, chamber music, choral music and opera, almost as if he were ticking off one genre after another. His approach to chamber music for strings with piano was similarly methodical, though reductive: a piano quintet was followed by a piano quartet, then piano trios, and then from 1 to 4 March 1851 he wrote his first piano and string duo: the Märchenbilder for viola and piano (also issued with an alternative violin solo part). He dedicated them to Wilhelm von Wasielewski, his concertmaster in Düsseldorf, who tried them out with Clara and two years later gave their first public performance. Schumann called these pieces mere “childish pranks” though this was probably just overcautious modesty. Not only was this his first solo work for viola, but also just about the first-ever solo viola work by any Romantic composer of note. Schumann initially couldn’t decide on a title, calling them “viola stories”, “fairy-tale songs” and finally “fairy-tale pictures”, though all of these refer to the narrative element inherent in them. The first and third pieces certainly seem to be “telling” us something, though we know not what; the second is a “hunting horn” rondo; and the fourth and last piece sounds like a Brahmsian lullaby avant la lettre (its main theme, incidentally, seems to hover behind the opening of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony, also in D).

Schumann wrote his First Violin Sonata, op 105 in a minor, in September 1851. Barely a month later he was writing a Second, this time in d minor. Where the First was in three movements, the Second is cast in four and is altogether more expansive. The slow opening is in a sarabande rhythm and reminiscent of the Chaconne from Bach’s Violin Partita in d minor (a work that Schumann knew well). The opening theme is generally agreed to be based on the surname of the dedicatee, the violinist Ferdinand David (with an “f” substituting for his “v”). The same theme opens the fast-paced movement proper, which is by turns passionate and lyrical, hesitant and agitated and veritably sweeps one along. The second movement, in b minor, is a “hunting” scherzo whose shift into the major towards the close is a magical moment that just about every critic agrees is Schumann at his best. The third movement is a set of variations in G major on a theme – first given pizzicato by the violin – that is a simple as it is memorable (some, incidentally, hear in it an echo of Luther’s chorale “I cry to thee in deepest need”). The last movement is in sonata form, and in its tempestuousness recalls the first movement. Schumann had published his First Sonata soon after its composition, so it was probably just the fear that he might swamp the market that made him hold back the Second for another two years. Despite the dedication to David, it was Joseph Joachim who gave the work’s first public performance in autumn 1853, organized roughly to coincide with its publication. Joachim loved it, writing to his friend Arnold Wehner on 10 September that “it is for me one of the loveliest creations of recent times in its magnificent unity and the concision of its themes. It is full of passion … The last movement is splendid in the way it ebbs and flows, and could be a landscape of the soul”. But just a few months after the composer’s death, Eduard Hanslick was already damning the Second Sonata as proof of Schumann’s declining powers. It suited Hanslick’s historical view of things to see a long, gradual decline instead of any abrupt biographical fracture. But the work itself merits no such nonsense. Had Schumann suddenly died in 1852 instead of dwindling away afterwards, Hanslick might well have joined Joachim in declaring the work “magnificent”; for that’s what it is.

Clara Schumann’s great fortune in life – as she saw it – was to fall in love and marry a composing genius. Her great misfortune in life – one might argue – was the same. Fêted as one of the leading pianists of her age, she was also a gifted composer, though outshone by her husband. Robert was outwardly supportive of her composing efforts, but since Clara also functioned as the conveyor belt for his babies he was of little concrete help to her career – she produced almost as many children as she did opus numbers during their marriage.

Clara’s Three Romances for violin and piano op. 22 were composed in July 1853 and dedicated to Joachim. They belong among her “last” works – after this year, she hardly ever composed again. In stylistic terms they are clearly situated in the Mendelssohnian/Schumannian tradition. But even where their mood might seem at first to reflect the bourgeois salon, phrases here and there are subtly elongated or shortened, little cross-rhythms come and go (as in the opening bars of No. 1) and unexpected harmonies intrude (such as the augmented chords in the final bars of No. 3) that altogether reveal a more complex sensibility. After Robert’s decline, Clara returned to her career as a piano virtuoso in order to feed the family. A pity she did not resume composing on a larger scale; the music world would have been the richer for it.

Chris Walton

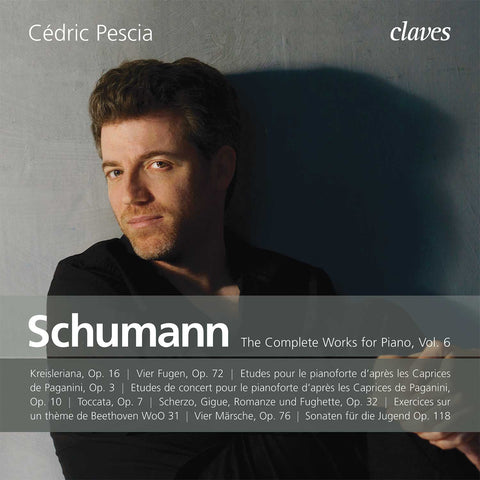

Return to the album | Read the booklet | Composer(s): Robert Schumann | Main Artist: Cédric Pescia