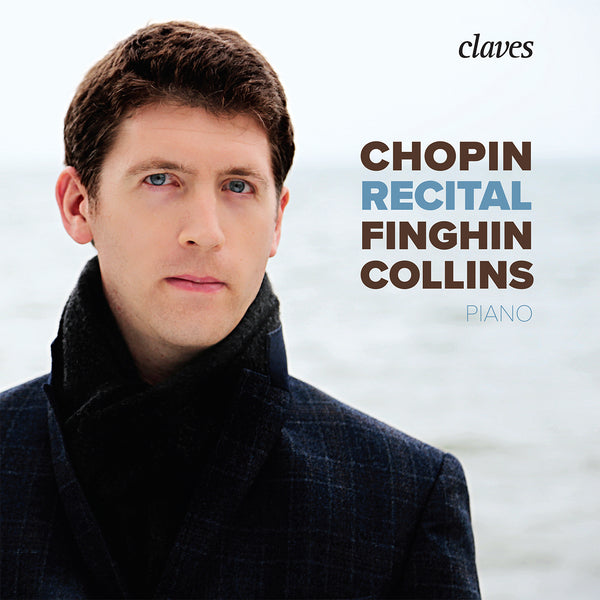

(2017) Chopin Recital - Finghin Collins, Piano

Kategorie(n): Piano

Instrument(e): Piano

Hauptkomponist: Frédéric Chopin

CD-Set: 1

Katalog Nr.:

CD 1719

Freigabe: 06.10.2017

EAN/UPC: 7619931171920

- UPC: 191773557874

Dieses Album ist jetzt neu aufgelegt worden. Bestellen Sie es jetzt zum Sonderpreis vor.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

Dieses Album ist noch nicht veröffentlicht worden. Bestellen Sie es jetzt vor.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

CHF 18.50

Inklusive MwSt. für die Schweiz und die EU

Kostenloser Versand

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

Inklusive MwSt. für die Schweiz und die EU

Kostenloser Versand

Dieses Album ist jetzt neu aufgelegt worden. Bestellen Sie es jetzt zum Sonderpreis vor.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

This album has not been released yet.

Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

SPOTIFY

(Verbinden Sie sich mit Ihrem Konto und aktualisieren die Seite, um das komplette Album zu hören)

CHOPIN RECITAL - FINGHIN COLLINS, PIANO

Official release date: 06.10.2017

Polonaise-Fantaisie in A flat Op 61

Chopin was a voluntary exile from his native Poland. Born into relative affluence in Żelazowa Wola west of Warsaw, his father Nicolas was French. Due partly to political upheaval, he left home when he was twenty. Staying for a while in Vienna, he secured a passport to Paris where he settled in October 1831. Once in situ, he became the idol of the aristocracy and was soon the friend of leading writers, painters and musicians. Yet, despite the glamorous and intellectual support of his surroundings, Chopin was lonely at heart. He expressed his nostalgia for Poland through his piano music in which he created a new idiom and performance technique.

Finghin Collins’s programme on this CD covers the major period of Chopin’s artistic activity and demonstrates the influence of Italian opera, particularly that of Bellini’s sophisticated bel canto style, and his own inherent dramatic impulses.

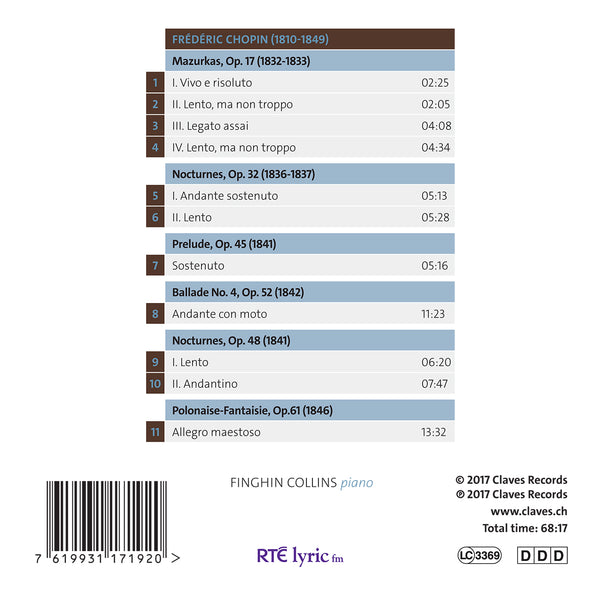

This begins with the Op 17 Mazurkas written in the early 1830s when Chopin was settling into Parisian life. Although he wrote over fifty Mazurkas, Robert Schumann maintained ‘few among them resemble each other [with] almost every one containing some poetic trait’. Finghin Collins’s choice of elegiac Nocturnes date from 1837 and 1841 when Chopin was the centre of Parisian cultural life. The stand-alone Prelude Op 45, with its feeling of improvisation, is also from 1841. One of Chopin’s greatest works, the F minor Ballade Op 52 is the most challenging of his four Ballades while the concluding Polonaise-Fantaisie Op 61 masterpiece comes from a particularly difficult period in the composer’s short life.

A traditional Polish dance, the Mazurka is in three-in-a-measure time, with an accentuation of the second beat and phrases ending on that beat. However, Chopin's Mazurkas are greatly refined with varying rhythms and tempi and occasionally introducing the characteristics of the related Kujawiak. The two dances, possibly local forms of the same thing, came from the Mazowsze and Kujawy provinces respectively. The first of the Op 17 set of four is marked Vivo e risoluto. In the robust and dynamic key of B flat major, it has two principal features intertwined. One is melodic, the other rhythmic. The brief and gentler central section moves into E flat major with its dolce rocking motion resembling Kujawy’s country musicians. The rather sad E minor Lento, ma non troppo Mazurka also recalls the Kujawiak. Its mood maybe suggests a traditional violinist skilled in extemporisation. The short middle section is livelier before the intricate patterns of the opening return to end the piece quietly. The A flat major Legato assai, is fused with Chopin’s instinctive touches. Running triplet figures enliven the vigorous E major central section. The final A minor Mazurka is actually more of a dance poem. Its anguished Lento, ma non troppo main theme seems to arrive from nowhere. A sense of mystery is, at times, disturbed by more realistic intrusions. A new motif, in the brighter A major key, appears and is repeated until it reaches a climactic outcry. The opening returns somewhat timidly and eventually dies away in the perdendosi closing bars.

Even if often morbidly sad, Chopin’s Nocturnes, influenced by those of Dublin-born John Field, are revered among his compositions. Reflecting his love of the mysteries of the night, they are ennobled with dramatic breadth, passion and grandeur. The expressive theme of the B major Op 32/1, marked Andante sostenuto, may possess an outer calm but there is underlying drama that surfaces in the unsettling concluding bars. In ternary form, its A flat major companion moves from an initial Lento into a more vigorous F minor central episode. When the principal idea returns Chopin marks it Appassionato. Orchestrated by Glazunov, this Nocturne assumed new life in the ballet Les Sylphides.

The C sharp minor Op 45 Prelude was completed at the writer George Sand’s villa at Nohant near Paris. Another masterpiece, the mood is set in the opening Sostenuto phrases. With two themes, the second has a more positive melodic line while a cadenza-like passage enjoys an ecstatic quality. The opening theme returns only to waft into oblivion.

Composed in 1842, Chopin’s Andantino con moto Fourth Ballade was revised the following year. As it progresses the music becomes increasingly rich and intricate with several connected themes developed simultaneously. The first of these, a haunting and mysterious valse triste, has a kind of Slavonic air to it. Stormy and dramatic octaves lead to the second subject, which resembles a barcarolle. This soon becomes more elaborate and is eventually interwoven into the first theme. Decorated and dazzling sections lead to a cadenza. Following this comes the astonishing power and intensity of the coda that concludes fff with four massive chords.

The two Op 48 Nocturnes may be described as ‘ballades in miniature’. The Lento C minor is a dramatic piece that begins mezza voce but grows with majestic gravitas. It moves into a rhapsodic recitative, which leads to a chorale that is developed with almost orchestral sonorities. The F sharp minor Andantino Nocturne brings welcome contrast in its extended and profound song-like theme. But matters change with the unexpected key of D flat major in the central Più lento. The music’s character is completely transformed.

Usually in triple time, the Polonaise is more of a procession than an actual dance. Like his Mazurkas, Chopin adapted it to serve his own artistic purposes and used it to express patriotism, chivalry and pageantry and, in the case of the A flat Polonaise-Fantaisie, his more secret thoughts and emotions. The piece dates from 1845/46 when the composer’s ten-year relationship with George Sand (Aurore Dupin, estranged wife of François Casimir Dudevant) was beginning to unravel. Written at her house at Nohant, the work has unusual breadth and structural novelty. Despite waywardness, the music follows a logical process in its ternary form construction. The broad introduction is a kind of meditative prelude opening out into the first section, which employs three thematic groups. The central sequence of ideas develops new subject matter while the final part is built essentially on the principal themes of the first and central sections. Chopin achieves an amazing sense of unity in the disparity of his material, which Liszt described as ‘being dominated by an elegiac sadness, broken here and there by gestures of consternation, melancholy smiles, sudden starts and restful passages fraught with tremblings’.

Pat O’Kelly

(2017) Chopin Recital - Finghin Collins, Piano - CD 1719

Official release date: 06.10.2017

Polonaise-Fantaisie in A flat Op 61

Chopin was a voluntary exile from his native Poland. Born into relative affluence in Żelazowa Wola west of Warsaw, his father Nicolas was French. Due partly to political upheaval, he left home when he was twenty. Staying for a while in Vienna, he secured a passport to Paris where he settled in October 1831. Once in situ, he became the idol of the aristocracy and was soon the friend of leading writers, painters and musicians. Yet, despite the glamorous and intellectual support of his surroundings, Chopin was lonely at heart. He expressed his nostalgia for Poland through his piano music in which he created a new idiom and performance technique.

Finghin Collins’s programme on this CD covers the major period of Chopin’s artistic activity and demonstrates the influence of Italian opera, particularly that of Bellini’s sophisticated bel canto style, and his own inherent dramatic impulses.

This begins with the Op 17 Mazurkas written in the early 1830s when Chopin was settling into Parisian life. Although he wrote over fifty Mazurkas, Robert Schumann maintained ‘few among them resemble each other [with] almost every one containing some poetic trait’. Finghin Collins’s choice of elegiac Nocturnes date from 1837 and 1841 when Chopin was the centre of Parisian cultural life. The stand-alone Prelude Op 45, with its feeling of improvisation, is also from 1841. One of Chopin’s greatest works, the F minor Ballade Op 52 is the most challenging of his four Ballades while the concluding Polonaise-Fantaisie Op 61 masterpiece comes from a particularly difficult period in the composer’s short life.

A traditional Polish dance, the Mazurka is in three-in-a-measure time, with an accentuation of the second beat and phrases ending on that beat. However, Chopin's Mazurkas are greatly refined with varying rhythms and tempi and occasionally introducing the characteristics of the related Kujawiak. The two dances, possibly local forms of the same thing, came from the Mazowsze and Kujawy provinces respectively. The first of the Op 17 set of four is marked Vivo e risoluto. In the robust and dynamic key of B flat major, it has two principal features intertwined. One is melodic, the other rhythmic. The brief and gentler central section moves into E flat major with its dolce rocking motion resembling Kujawy’s country musicians. The rather sad E minor Lento, ma non troppo Mazurka also recalls the Kujawiak. Its mood maybe suggests a traditional violinist skilled in extemporisation. The short middle section is livelier before the intricate patterns of the opening return to end the piece quietly. The A flat major Legato assai, is fused with Chopin’s instinctive touches. Running triplet figures enliven the vigorous E major central section. The final A minor Mazurka is actually more of a dance poem. Its anguished Lento, ma non troppo main theme seems to arrive from nowhere. A sense of mystery is, at times, disturbed by more realistic intrusions. A new motif, in the brighter A major key, appears and is repeated until it reaches a climactic outcry. The opening returns somewhat timidly and eventually dies away in the perdendosi closing bars.

Even if often morbidly sad, Chopin’s Nocturnes, influenced by those of Dublin-born John Field, are revered among his compositions. Reflecting his love of the mysteries of the night, they are ennobled with dramatic breadth, passion and grandeur. The expressive theme of the B major Op 32/1, marked Andante sostenuto, may possess an outer calm but there is underlying drama that surfaces in the unsettling concluding bars. In ternary form, its A flat major companion moves from an initial Lento into a more vigorous F minor central episode. When the principal idea returns Chopin marks it Appassionato. Orchestrated by Glazunov, this Nocturne assumed new life in the ballet Les Sylphides.

The C sharp minor Op 45 Prelude was completed at the writer George Sand’s villa at Nohant near Paris. Another masterpiece, the mood is set in the opening Sostenuto phrases. With two themes, the second has a more positive melodic line while a cadenza-like passage enjoys an ecstatic quality. The opening theme returns only to waft into oblivion.

Composed in 1842, Chopin’s Andantino con moto Fourth Ballade was revised the following year. As it progresses the music becomes increasingly rich and intricate with several connected themes developed simultaneously. The first of these, a haunting and mysterious valse triste, has a kind of Slavonic air to it. Stormy and dramatic octaves lead to the second subject, which resembles a barcarolle. This soon becomes more elaborate and is eventually interwoven into the first theme. Decorated and dazzling sections lead to a cadenza. Following this comes the astonishing power and intensity of the coda that concludes fff with four massive chords.

The two Op 48 Nocturnes may be described as ‘ballades in miniature’. The Lento C minor is a dramatic piece that begins mezza voce but grows with majestic gravitas. It moves into a rhapsodic recitative, which leads to a chorale that is developed with almost orchestral sonorities. The F sharp minor Andantino Nocturne brings welcome contrast in its extended and profound song-like theme. But matters change with the unexpected key of D flat major in the central Più lento. The music’s character is completely transformed.

Usually in triple time, the Polonaise is more of a procession than an actual dance. Like his Mazurkas, Chopin adapted it to serve his own artistic purposes and used it to express patriotism, chivalry and pageantry and, in the case of the A flat Polonaise-Fantaisie, his more secret thoughts and emotions. The piece dates from 1845/46 when the composer’s ten-year relationship with George Sand (Aurore Dupin, estranged wife of François Casimir Dudevant) was beginning to unravel. Written at her house at Nohant, the work has unusual breadth and structural novelty. Despite waywardness, the music follows a logical process in its ternary form construction. The broad introduction is a kind of meditative prelude opening out into the first section, which employs three thematic groups. The central sequence of ideas develops new subject matter while the final part is built essentially on the principal themes of the first and central sections. Chopin achieves an amazing sense of unity in the disparity of his material, which Liszt described as ‘being dominated by an elegiac sadness, broken here and there by gestures of consternation, melancholy smiles, sudden starts and restful passages fraught with tremblings’.

Pat O’Kelly

Return to the album | Read the booklet | Composer(s): Frédéric Chopin | Main Artist: Finghin Collins