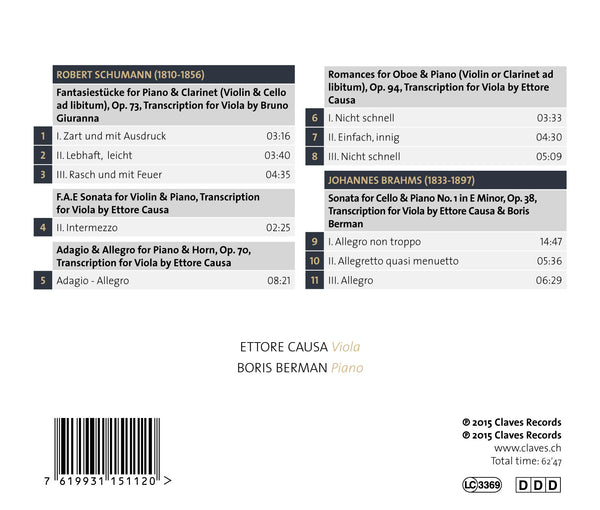

(2015) Brahms & Schumann: Transcriptions for Viola & Piano - Ettore Causa, Boris Berman

Kategorie(n): Kammermusik Piano

Instrument(e): Piano Viola

Hauptkomponist: Robert Schumann

CD-Set: 1

Katalog Nr.:

CD 1511

Freigabe: 13.11.2015

EAN/UPC: 7619931151120

- UPC: 889176654961

Dieses Album ist jetzt neu aufgelegt worden. Bestellen Sie es jetzt zum Sonderpreis vor.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

Dieses Album ist noch nicht veröffentlicht worden. Bestellen Sie es jetzt vor.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

CHF 18.50

Inklusive MwSt. für die Schweiz und die EU

Kostenloser Versand

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

Inklusive MwSt. für die Schweiz und die EU

Kostenloser Versand

Dieses Album ist jetzt neu aufgelegt worden. Bestellen Sie es jetzt zum Sonderpreis vor.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

This album has not been released yet.

Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

SPOTIFY

(Verbinden Sie sich mit Ihrem Konto und aktualisieren die Seite, um das komplette Album zu hören)

BRAHMS & SCHUMANN: TRANSCRIPTIONS FOR VIOLA & PIANO - ETTORE CAUSA, BORIS BERMAN

Schumann in fact had a history of proceeding with bureaucratic thoroughness through different genres. Since marrying in 1840, he had abandoned his bachelor penchant for wild, semi-formless, quasi-fragmentary piano works. He spent his first year of marriage composing songs, and this was followed by a “symphonic year” (1841), a “string quartet year” (1842) and an “oratorio year” (1843), as if he were ticking off a “to-do” list as befitting a serious German composer in the post-Beethovenian mould. After an interruption of two years on grounds of dodgy mental health he turned to dramatic works (including his only opera, Genoveva) and then, in early 1849, to the instrumental duos with piano that prompted Clara’s enthusiastic diary entry quoted above.

Schumann’s duos for wind instruments and piano were highly innovative at the time. While contemporary lists of music publications (“Hofmeisters Monatsberichte”) confirm that thousands of editions were being churned out by publishers large and small in mid-19th-century Central Europe, these included hardly any independent works for the wind-and-piano duo combinations that were now the focus of Schumann’s attention. Apart from Beethoven’s early Horn Sonata and Weber’s Grand Duo for clarinet, no Classical or Romantic composers of consequence had written any piano duos with those instruments until Schumann, and the solo oboe repertoire was virtually non-existent. Schumann seems to have acted as a trendsetter – for after publishing his Fantasy Pieces op. 73 for clarinet and piano, Luckhardt of Kassel brought out two further sets of “fantasy pieces” for the same instruments over the next two years (by Carl Reinecke and Johann Carl Eschmann).

(2015) Brahms & Schumann: Transcriptions for Viola & Piano - Ettore Causa, Boris Berman - CD 1511

“Now all instruments will have their turn” wrote Clara Schumann in her diary in early 1849. Her husband Robert had just finished two sets of duos with piano: one for clarinet, the next for horn (the Fantasy Pieces op. 73 and the Adagio and Allegro op. 70 recorded here), and he had made clear to her his intention to proceed in similar fashion across the instrumental spectrum. This was an exaggeration, for Schumann wasn’t some Romantic proto-Hindemith determined to fertilize every instrument with a sonata of his seed, and his attention was soon diverted towards choral and orchestral works. Nevertheless, 1849 did see him compose two more duos – for cello and piano (op. 102) and for oboe and piano (the Romances op. 94, recorded here).

Schumann in fact had a history of proceeding with bureaucratic thoroughness through different genres. Since marrying in 1840, he had abandoned his bachelor penchant for wild, semi-formless, quasi-fragmentary piano works. He spent his first year of marriage composing songs, and this was followed by a “symphonic year” (1841), a “string quartet year” (1842) and an “oratorio year” (1843), as if he were ticking off a “to-do” list as befitting a serious German composer in the post-Beethovenian mould. After an interruption of two years on grounds of dodgy mental health he turned to dramatic works (including his only opera, Genoveva) and then, in early 1849, to the instrumental duos with piano that prompted Clara’s enthusiastic diary entry quoted above.

Schumann’s duos for wind instruments and piano were highly innovative at the time. While contemporary lists of music publications (“Hofmeisters Monatsberichte”) confirm that thousands of editions were being churned out by publishers large and small in mid-19th-century Central Europe, these included hardly any independent works for the wind-and-piano duo combinations that were now the focus of Schumann’s attention. Apart from Beethoven’s early Horn Sonata and Weber’s Grand Duo for clarinet, no Classical or Romantic composers of consequence had written any piano duos with those instruments until Schumann, and the solo oboe repertoire was virtually non-existent. Schumann seems to have acted as a trendsetter – for after publishing his Fantasy Pieces op. 73 for clarinet and piano, Luckhardt of Kassel brought out two further sets of “fantasy pieces” for the same instruments over the next two years (by Carl Reinecke and Johann Carl Eschmann).

Return to the album | Read the booklet | Composer(s): Robert Schumann | Main Artist: Ettore Causa