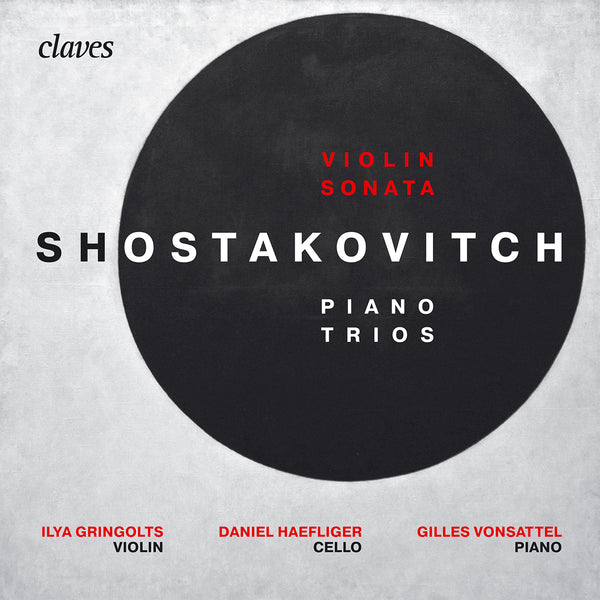

(2017) Shostakovitch : Piano Trios & Violin Sonata

Kategorie(n): Kammermusik Piano

Instrument(e): Violoncello Piano Geige

Hauptkomponist: Dmitri Shostakovich

CD-Set: 1

Katalog Nr.:

CD 1817

Freigabe: 22.12.2017

EAN/UPC: 7619931181721

Dieses Album ist jetzt neu aufgelegt worden. Bestellen Sie es jetzt zum Sonderpreis vor.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

Dieses Album ist noch nicht veröffentlicht worden. Bestellen Sie es jetzt vor.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

CHF 18.50

Inklusive MwSt. für die Schweiz und die EU

Kostenloser Versand

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

Inklusive MwSt. für die Schweiz und die EU

Kostenloser Versand

Dieses Album ist jetzt neu aufgelegt worden. Bestellen Sie es jetzt zum Sonderpreis vor.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

This album has not been released yet.

Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

SPOTIFY

(Verbinden Sie sich mit Ihrem Konto und aktualisieren die Seite, um das komplette Album zu hören)

SHOSTAKOVITCH : PIANO TRIOS & VIOLIN SONATA

*** Clé du Mois ResMusica ***

This music draws incredible strength from the violent intersection of an overpowering will to live and the inevitability of death. First comes hope, tenderness, magical and miraculous flights. Followed by sarcasm, irony, revolt. And finally nostalgia, sluggishness, despair, and the hopeless aspect of an opaque hereafter with no return. As Shostakovich himself said, « If you play my music well, flies should drop dead. » The despair that grows ceaselessly throughout his work can become unbearable – it must be experienced in concert.

Extreme situations can open paths to understanding and revelation. Here, they can be summarized by the following paradox: nowhere have I encountered anyone speak to me about death in such a bracing, powerful and vibrant way.

Daniel Haefliger

***

In July 1917, during a demonstration in Petrograd, a boy was killed by the Tsarist forces before the young Dmitri Shostakovich’s very eyes. Deeply shocked, Shostakovich thereupon composed a Funeral March in remembrance of the victims of the Revolution. He would then live through World War I, the October Revolution, the civil war, Stalin’s Great Purge, World War II, and new purges, among others. Violence, despair, tyranny and death are omnipresent in his existence and appear in his music. The three works chosen by Ilya Gringolts, Daniel Haefliger and Gilles Vonsattel for this recording pay tribute to this entire experience, coming from the composer’s youth, his mature years, and his final period.

Composed in the autumn of 1923 during his studies at the Petrograd Conservatory, the first Trio op. 8 marks Shostakovich’s real debut as a composer. On the surface, this was a disappointment, since both audience and critics gave the work a cold welcome, deeming it immature and affected. The young composer, deeply hurt and discouraged, considered it pointless to edit the manuscript for publishing – even leaving out the last 22 bars of the piano part. It was only completed in 1983, by his pupil Boris I. Tischtschenko. Compared with Shostakovich’s total production, this work, full of youth and energy, fascinates by way of its strength and expressive clarity. It already contains all the characteristic stylistic traits of the composer’s style.

The second Trio op. 67, composed 21 years later, is dedicated to the memory of Ivan Sollertinski, Shostakovich’s “dearest and closest friend”, who died suddenly in February 1944 at the age of 41. The first movement, Andante, begins with a disquieting melody on the cello con sordino in high pitched harmonics, joined in canon by the violin playing in its lowest register almost two octaves lower than the cello, and later by the piano, an octave and a half below the violin. The extreme distance between the registers and the unusual choice of timbres transport us into a strange and bewitching world. The scherzo, Allegro con brio, takes on the appearance of a frenzied, wildly fast dance, spectacular and sarcastic. The Largo, a funeral march in the form of a passacaglia, imperturbably repeats the same series of chords six times on the piano, from which poignant lamentations come forth in successive waves, carried by the violin and cello. An inescapable and obsessive sense of beauty derives from it. The almost orchestral Finale, Allegretto, is born again out of a death dance, both heroic and disillusioned. It is the first time Shostakovich uses a Hebrew theme in his music, as if his own individual mourning was paired with a “generalised” mourning for the Jewish nation, whose extermination by the Nazis he had recently learned of. The first quavers, repeated pp staccato on the piano, send a chill down the spine, the violin then presents a short dance motif, at once macabre and desperate, taken up by the cello and the piano, alternating with a strange and unbalanced five beat waltz. At the most frenzied point, the dance is suddenly interrupted by a cascade of arpeggios on the piano, made up of the passacaglia theme from the 2nd movement, into which the violin plays simulaneously the theme of the 1st movement. The trio ends with a large coda that finally leads to a brief moment of peace, only in the last few bars.

Shostakovich composed his unique Violin Sonata op. 134 in the autumn of 1968, during a period of extreme political repression in the USSR, while Warsaw Pact troops invaded Czechoslovakia, crushing the hopes of the Prague Spring. The work is a reflection of this brutal reality. Although it makes abundant use of twelve-tone systems, it is not serial: Shostakovich was in fact only interested in dodecaphonism from a thematic point of view and to put into perspective strong key signatures, deriving a unique expressive tension from this opposition. The 1st movement starts with a tone row to which the violin answers with the motif D - E flat - D flat - C - B, which, in the German notation, corresponds to DS(Des)CH, ie the composer’s initials with a slight modification. The tone row and motif are then transformed according to the rules of counterpoint finally to create a figure reminiscent of the chiming of a death knell. The 2nd movement is a Hebrew nuptial dance, but rather than being festive, it rapidly becomes a desperate and fiendish diabolic struggle between the two instruments. The music stops abruptly like the tanks halting any aspiration to freedom in August 1968. The final Largo, a series of variations, brings us back to the world of J.S. Bach, whom Shostakovich revered as a master and inspiration. This movement condenses the previous elements of the work through compositional techniques such as counterpoint, quotations and the tone row that opened the entire sonata, thus concluding the cycle.

Hildegard Stauder-Bilicki

Translated from french by Isabelle Watson

The Artists

A versatile musician, Daniel Haefliger has distinguished himself over the course of his career as a soloist, chamber musician and teacher as well as organiser, lecturer and translator, and has also initiated numerous educational and musicological projects.

A cellist trained by Pierre Fournier and André Navarra, he has performed regularly in major musical centres such as Berlin, London, Lucerne, Paris, Tokyo and Sydney with partners such as Heinz Holliger, Dénes Várjon and Patricia Kopatchinskaja and conductors such as Thierry Fischer, Pascal Rophé, Peter Eötvös and Magnus Lindberg. He has criss-crossed Europe with the Zehetmair Quartet, which has won the world's highest recording awards and whose distinctive feature is that it plays all its programmes by heart.

Deeply committed to the music of his time, he has worked closely with all the composers who have marked his generation, including György Kurtág, Brian Ferneyhough, György Ligeti, Elliott Carter, Heinz Holliger, Helmut Lachenmann, Klaus Huber, Luciano Berio, Franco Donatoni, Pascal Dusapin, George Benjamin and many others, and continues to commission and premiere numerous works by the new generation of Swiss composers.

At the turn of the millennium, he initiated Switzerland's largest chamber music series, the Swiss Chamber Concerts, with regular concerts in Geneva, Zurich, Basel and Lugano, and is its musical and administrative director.

He has been solo cellist with the Ensemble Modern in Frankfurt, the Camerata Bern and the Ensemble Contrechamps, among others. He is also a founding member of the musicological publishing house of the same name, and has translated the correspondence between Schönberg and Kandinsky into French.

A keen teacher, he teaches chamber music at the HEMU in Lausanne and Sion, and in 2014 founded the Swiss Chamber Academy, followed in 2017 by the Swiss Chamber Camerata, which brings together the most promising Swiss talent.

Numerous radio and CD recordings with labels such as Forlane (F), Stradivarius (I), Claves (CH), Neos (D), ECM (D) and Genuin (D) bear witness to his activities as a performer.

Daniel Haefliger plays an instrument by Milanese luthier Giovanni Grancino (1698).

***

Born in Lausanne in 1981, pianist Gilles Vonsattel completed his training in the United States at the Juilliard School with Jerome Lowenthal. He made a name for himself internationally by winning the famous Naumburg Competition in New York City and the Geneva Competition. He performs regularly in venues such as Alice Tully Hall (New York), the Tonhalle (Zürich), Victoria Hall (Geneva), the Gasteig (Munich) and Wigmore Hall (London). He has also performed at festivals such as Rockport, Seattle, Caramoor, Spoleto USA, Music@Menlo, Tanglewood, West Cork, Archipelago, Ravinia and La Roque d'Anthéron. He has been a guest with orchestras such as the Boston Symphony, San Francisco Symphony, Chicago Symphony, Münchner Philharmoniker and Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra.

In 2008, Gilles Vonsattel was awarded the prestigious Avery Fisher career grant. He is currently a member of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center in New York and regularly collaborates with artists such as Kim Kashkashian, Gary Hoffman, Ida Kavafian, Paul Watkins, Paul Neubauer, David Shifrin, Emmanuel Pahud, Quatuor Ebène, Danish Quartet, Escher Quartet and Yo-Yo Ma. Very active in the world of contemporary music, he has worked with composers such as Heinz Holliger, Jörg Widmann and George Benjamin, and has taken part in numerous premieres. His recording (2011) for Honens/Naxos consisting of works by Debussy, Ravel, Honegger and Holliger was named one of the best discs of the year by Timeout New York, and his disc ‘Shadowlines’ (2015), which surrounds George Benjamin's work of the same name with music by Scarlatti, Messiaen, Webern and Debussy, received rave reviews from the New York Times and Gramophone UK.

***

Despite his young age, Ilya Gringolts has long enjoyed a brilliant international career. After studying violin (at the Juilliard School with Itzhak Perlman) and composition, he won the ‘Premio Paganini’ international competition in 1998, becoming the youngest winner in the competition's history. In 2008, he founded the Gringolts Quartet. As a soloist, he has devoted himself to contemporary music, participating in the creation of works by Peter Maxwell Davies, Augusta Read Thomas, Christophe Bertrand and Michael Jarrell. An enthusiast of early music, he performs the complete cycle of Bach sonatas on the baroque violin. He performs with world-renowned orchestras such as the Bamberger Symphoniker, the Copenhagen Philharmonic and the BBC Scottish Symphony. As a chamber musician, his partners include Yuri Bashmet, Nicolas Angelich, Itamar Golan, Jörg Widmann and Maxim Vengerov.

Ilya Gringolts has recorded for Deutsche Grammophon, Hyperion, Onyx and Orchid Classic, with Mikhail Pletnev, Vadim Repin, Nobuko Imai and Lynn Harrell (Schumann, Brahms, Paganini, Weinberg etc.). Professor of violin at the Zürcher Hochschule der Künste, he also teaches regularly at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama in Glasgow.

He plays a Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ from 1742-1743 on loan from a private collector.

*** Clé du Mois ResMusica ***

This music draws incredible strength from the violent intersection of an overpowering will to live and the inevitability of death. First comes hope, tenderness, magical and miraculous flights. Followed by sarcasm, irony, revolt. And finally nostalgia, sluggishness, despair, and the hopeless aspect of an opaque hereafter with no return. As Shostakovich himself said, « If you play my music well, flies should drop dead. » The despair that grows ceaselessly throughout his work can become unbearable – it must be experienced in concert.

Extreme situations can open paths to understanding and revelation. Here, they can be summarized by the following paradox: nowhere have I encountered anyone speak to me about death in such a bracing, powerful and vibrant way.

Daniel Haefliger

***

In July 1917, during a demonstration in Petrograd, a boy was killed by the Tsarist forces before the young Dmitri Shostakovich’s very eyes. Deeply shocked, Shostakovich thereupon composed a Funeral March in remembrance of the victims of the Revolution. He would then live through World War I, the October Revolution, the civil war, Stalin’s Great Purge, World War II, and new purges, among others. Violence, despair, tyranny and death are omnipresent in his existence and appear in his music. The three works chosen by Ilya Gringolts, Daniel Haefliger and Gilles Vonsattel for this recording pay tribute to this entire experience, coming from the composer’s youth, his mature years, and his final period.

Composed in the autumn of 1923 during his studies at the Petrograd Conservatory, the first Trio op. 8 marks Shostakovich’s real debut as a composer. On the surface, this was a disappointment, since both audience and critics gave the work a cold welcome, deeming it immature and affected. The young composer, deeply hurt and discouraged, considered it pointless to edit the manuscript for publishing – even leaving out the last 22 bars of the piano part. It was only completed in 1983, by his pupil Boris I. Tischtschenko. Compared with Shostakovich’s total production, this work, full of youth and energy, fascinates by way of its strength and expressive clarity. It already contains all the characteristic stylistic traits of the composer’s style.

The second Trio op. 67, composed 21 years later, is dedicated to the memory of Ivan Sollertinski, Shostakovich’s “dearest and closest friend”, who died suddenly in February 1944 at the age of 41. The first movement, Andante, begins with a disquieting melody on the cello con sordino in high pitched harmonics, joined in canon by the violin playing in its lowest register almost two octaves lower than the cello, and later by the piano, an octave and a half below the violin. The extreme distance between the registers and the unusual choice of timbres transport us into a strange and bewitching world. The scherzo, Allegro con brio, takes on the appearance of a frenzied, wildly fast dance, spectacular and sarcastic. The Largo, a funeral march in the form of a passacaglia, imperturbably repeats the same series of chords six times on the piano, from which poignant lamentations come forth in successive waves, carried by the violin and cello. An inescapable and obsessive sense of beauty derives from it. The almost orchestral Finale, Allegretto, is born again out of a death dance, both heroic and disillusioned. It is the first time Shostakovich uses a Hebrew theme in his music, as if his own individual mourning was paired with a “generalised” mourning for the Jewish nation, whose extermination by the Nazis he had recently learned of. The first quavers, repeated pp staccato on the piano, send a chill down the spine, the violin then presents a short dance motif, at once macabre and desperate, taken up by the cello and the piano, alternating with a strange and unbalanced five beat waltz. At the most frenzied point, the dance is suddenly interrupted by a cascade of arpeggios on the piano, made up of the passacaglia theme from the 2nd movement, into which the violin plays simulaneously the theme of the 1st movement. The trio ends with a large coda that finally leads to a brief moment of peace, only in the last few bars.

Shostakovich composed his unique Violin Sonata op. 134 in the autumn of 1968, during a period of extreme political repression in the USSR, while Warsaw Pact troops invaded Czechoslovakia, crushing the hopes of the Prague Spring. The work is a reflection of this brutal reality. Although it makes abundant use of twelve-tone systems, it is not serial: Shostakovich was in fact only interested in dodecaphonism from a thematic point of view and to put into perspective strong key signatures, deriving a unique expressive tension from this opposition. The 1st movement starts with a tone row to which the violin answers with the motif D - E flat - D flat - C - B, which, in the German notation, corresponds to DS(Des)CH, ie the composer’s initials with a slight modification. The tone row and motif are then transformed according to the rules of counterpoint finally to create a figure reminiscent of the chiming of a death knell. The 2nd movement is a Hebrew nuptial dance, but rather than being festive, it rapidly becomes a desperate and fiendish diabolic struggle between the two instruments. The music stops abruptly like the tanks halting any aspiration to freedom in August 1968. The final Largo, a series of variations, brings us back to the world of J.S. Bach, whom Shostakovich revered as a master and inspiration. This movement condenses the previous elements of the work through compositional techniques such as counterpoint, quotations and the tone row that opened the entire sonata, thus concluding the cycle.

Hildegard Stauder-Bilicki

Translated from french by Isabelle Watson

The Artists

A versatile musician, Daniel Haefliger has distinguished himself over the course of his career as a soloist, chamber musician and teacher as well as organiser, lecturer and translator, and has also initiated numerous educational and musicological projects.

A cellist trained by Pierre Fournier and André Navarra, he has performed regularly in major musical centres such as Berlin, London, Lucerne, Paris, Tokyo and Sydney with partners such as Heinz Holliger, Dénes Várjon and Patricia Kopatchinskaja and conductors such as Thierry Fischer, Pascal Rophé, Peter Eötvös and Magnus Lindberg. He has criss-crossed Europe with the Zehetmair Quartet, which has won the world's highest recording awards and whose distinctive feature is that it plays all its programmes by heart.

Deeply committed to the music of his time, he has worked closely with all the composers who have marked his generation, including György Kurtág, Brian Ferneyhough, György Ligeti, Elliott Carter, Heinz Holliger, Helmut Lachenmann, Klaus Huber, Luciano Berio, Franco Donatoni, Pascal Dusapin, George Benjamin and many others, and continues to commission and premiere numerous works by the new generation of Swiss composers.

At the turn of the millennium, he initiated Switzerland's largest chamber music series, the Swiss Chamber Concerts, with regular concerts in Geneva, Zurich, Basel and Lugano, and is its musical and administrative director.

He has been solo cellist with the Ensemble Modern in Frankfurt, the Camerata Bern and the Ensemble Contrechamps, among others. He is also a founding member of the musicological publishing house of the same name, and has translated the correspondence between Schönberg and Kandinsky into French.

A keen teacher, he teaches chamber music at the HEMU in Lausanne and Sion, and in 2014 founded the Swiss Chamber Academy, followed in 2017 by the Swiss Chamber Camerata, which brings together the most promising Swiss talent.

Numerous radio and CD recordings with labels such as Forlane (F), Stradivarius (I), Claves (CH), Neos (D), ECM (D) and Genuin (D) bear witness to his activities as a performer.

Daniel Haefliger plays an instrument by Milanese luthier Giovanni Grancino (1698).

***

Born in Lausanne in 1981, pianist Gilles Vonsattel completed his training in the United States at the Juilliard School with Jerome Lowenthal. He made a name for himself internationally by winning the famous Naumburg Competition in New York City and the Geneva Competition. He performs regularly in venues such as Alice Tully Hall (New York), the Tonhalle (Zürich), Victoria Hall (Geneva), the Gasteig (Munich) and Wigmore Hall (London). He has also performed at festivals such as Rockport, Seattle, Caramoor, Spoleto USA, Music@Menlo, Tanglewood, West Cork, Archipelago, Ravinia and La Roque d'Anthéron. He has been a guest with orchestras such as the Boston Symphony, San Francisco Symphony, Chicago Symphony, Münchner Philharmoniker and Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra.

In 2008, Gilles Vonsattel was awarded the prestigious Avery Fisher career grant. He is currently a member of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center in New York and regularly collaborates with artists such as Kim Kashkashian, Gary Hoffman, Ida Kavafian, Paul Watkins, Paul Neubauer, David Shifrin, Emmanuel Pahud, Quatuor Ebène, Danish Quartet, Escher Quartet and Yo-Yo Ma. Very active in the world of contemporary music, he has worked with composers such as Heinz Holliger, Jörg Widmann and George Benjamin, and has taken part in numerous premieres. His recording (2011) for Honens/Naxos consisting of works by Debussy, Ravel, Honegger and Holliger was named one of the best discs of the year by Timeout New York, and his disc ‘Shadowlines’ (2015), which surrounds George Benjamin's work of the same name with music by Scarlatti, Messiaen, Webern and Debussy, received rave reviews from the New York Times and Gramophone UK.

***

Despite his young age, Ilya Gringolts has long enjoyed a brilliant international career. After studying violin (at the Juilliard School with Itzhak Perlman) and composition, he won the ‘Premio Paganini’ international competition in 1998, becoming the youngest winner in the competition's history. In 2008, he founded the Gringolts Quartet. As a soloist, he has devoted himself to contemporary music, participating in the creation of works by Peter Maxwell Davies, Augusta Read Thomas, Christophe Bertrand and Michael Jarrell. An enthusiast of early music, he performs the complete cycle of Bach sonatas on the baroque violin. He performs with world-renowned orchestras such as the Bamberger Symphoniker, the Copenhagen Philharmonic and the BBC Scottish Symphony. As a chamber musician, his partners include Yuri Bashmet, Nicolas Angelich, Itamar Golan, Jörg Widmann and Maxim Vengerov.

Ilya Gringolts has recorded for Deutsche Grammophon, Hyperion, Onyx and Orchid Classic, with Mikhail Pletnev, Vadim Repin, Nobuko Imai and Lynn Harrell (Schumann, Brahms, Paganini, Weinberg etc.). Professor of violin at the Zürcher Hochschule der Künste, he also teaches regularly at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama in Glasgow.

He plays a Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ from 1742-1743 on loan from a private collector.

Return to the album | Read the booklet | Composer(s): Dmitri Shostakovich | Main Artist: Ilya Gringolts

STUDIO-MASTER (HOCHAUFLÖSENDES AUDIO)

Alle Alben

Amethys Design

Auf Lager

Clé du mois - ResMusica

Daniel Haefliger

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Geige

Gilles Vonsattel

High-resolution audio - Studio master quality

ICMA 2019

Ilya Gringolts

Kammermusik

Klavier

Populäre Alben

Releases 2015 - 2017

Swiss Chamber Soloists

Violoncello

Alle Alben

Amethys Design

Auf Lager

Clé du mois - ResMusica

Daniel Haefliger

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Geige

Gilles Vonsattel

High-resolution audio - Studio master quality

ICMA 2019

Ilya Gringolts

Kammermusik

Klavier

Populäre Alben

Releases 2015 - 2017

Swiss Chamber Soloists

Violoncello