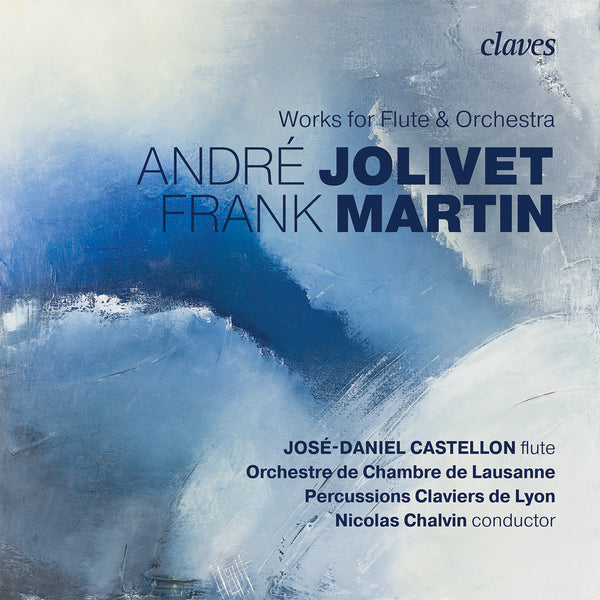

(2019) Martin & Jolivet: Works for Flute & Orchestra

Kategorie(n): Kammermusik Repertoire

Instrument(e): Flöte Geige

Hauptkomponist: André Jolivet

Orchester: Orchestre de Chambre de Lausanne

Dirigent: Nicolas Chalvin

CD-Set: 1

Katalog Nr.:

CD 1818

Freigabe: 10.05.2019

EAN/UPC: 7619931181820

Dieses Album ist jetzt neu aufgelegt worden. Bestellen Sie es jetzt zum Sonderpreis vor.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

Dieses Album ist noch nicht veröffentlicht worden. Bestellen Sie es jetzt vor.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

CHF 18.50

Inklusive MwSt. für die Schweiz und die EU

Kostenloser Versand

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

Inklusive MwSt. für die Schweiz und die EU

Kostenloser Versand

Dieses Album ist jetzt neu aufgelegt worden. Bestellen Sie es jetzt zum Sonderpreis vor.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

This album has not been released yet.

Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

SPOTIFY

(Verbinden Sie sich mit Ihrem Konto und aktualisieren die Seite, um das komplette Album zu hören)

MARTIN & JOLIVET: WORKS FOR FLUTE & ORCHESTRA

One being Swiss, the other one French, both have traveled throughout the twentieth century without really knowing each other, nevertheless they have shared an extraordinary amount of similarities.

Even though Frank Martin was 15 years older, they have both perished only one month apart at the end of 1974 and have therefore lived in parallel for almost the whole twentieth century. In the same manner, both received a solid musical education at first and later on seen their parents were opposed to their aspirations in making a living as musicians and therefore obliging their sons to choose, at first, an alternative profession to satisfy their families demands.

Both composers display in their music a great deal of mysticism or even fervent faith, which is frankly Christian with Martin and much more esoteric when it comes to Jolivet who was passionate about several thesis of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin.

They have expressed their spirituality in numerous works that were in terms of form quite conventional for their time (Oratorio, Cantata, Requiem Mass...). However, they have found a way to express it in much more unexpected musical forms, such as Frank Martin’s Sonata da Chiesa to which we will come back later, or Incantations written in 1936, which Jolivet wrote for the Flute alone and whose mystical dimension cannot be missed by anyone nowadays.

From a purely musical point of view, either of the two composers have found themselves entirely submerged into any of the so-called avant-garde movements that were predominant in the first half of the twentieth century. Without ignoring the fact that they have both used certain aspects of serialism, they have never completely renounced the concept of tonality and even though they have always stayed attached to the importance of melody, each of them has eventually found their own musical voice that cannot be reduced to any form of neoclassicism. Nonetheless, when considering the incantatory, wild or even violent aspects of André Jolivet’s music, one could consider that he has introduced the concept of Primitivism, if ever this movement even existed in the musical sphere.

As most flutists, I am particularly keen on Frank Martin’s music and even more so for André Jolivet’s who has enriched our repertoire. Even though both wrote marvelous pieces for our instrument, their individual approach towards it is quite different.

Even though Frank Martin was married to a flutist (Maria Martin) for a major part of his life, he has composed only few works where the flute is brought to the foreground. His Ballade has nonetheless become one of the most frequently performed works for flute. This masterpiece begins with an extremely expressive first movement, full of tension and anguish, while the second movement is fast, rhythmical and virtuosic (fireworks was the word critic once used to flatter my interpretation!). The historical value of the Ballade is worth mentioning as well since it was written for the Geneva International Music Competition in 1939, a year that can easily describe the gloomy and anguished atmosphere of the piece.

The Sonata da Chiesa, less famous, was originally conceived in 1938 for viola d’amore and organ. Shortly after, Frank Martin finalized the first arrangement for flute and organ, dedicated to his wife Maria, Victor Desarzens arranged the piece for flute and strings in 1958.

Victor Desarzens being a immense admirer of Frank Martin, found the energy and resources to give the first performance of the work with the Lausanne Chamber Orchestra in the middle of the Second World War. During three decades of service as the music director of Lausanne’s principal orchestra, he programmed 37 performances of Frank Martin’s works (more than those of Robert Schumann and as much as those of Franz Schubert!). Throughout their fruitful collaboration, both men became great friends.

Even though Desarzens loved the Ballade, he considered it a bit too short to be presented alone and therefore concieved his arrangement of Sonata da Chiesa in order to be able to perform both pieces consecutively. The “premiere” of this version took place the 18th of January 1959 with the flutist Marianne Clément being accompanied by the Lausanne Chamber Orchestra, led by its principal conductor. Frank Martin was indeed very pleased with the performance. The sound of a string orchestra enables a true contrast between the soloist and the accompaniment and brings to the score a new energy and breath. And lastly, the new arrangement now enabled more possibilites of execution, given the fact that organ is not present in all concert halls.

By contrast, the flute plays a central role in the catalog of André Jolivet’s works. For him, it is an instrument unlike any other: “The flute is close to nature, animated by the breath which is the vehicle of psychism and the emanation of the most profound being. It is a prime example of a musical instrument since it is essentially composed of a pierced hollow tube. Thanks to its simplicity it enables musicians to express their most profound feelings. It is therefore, besides the human voice, the most natural and the most ancient musical instrument. I think that the flute is the best means to communicate the feelings that connect us not only to our peers or any beings that have lived on the Earth, but to the ensemble of the forces that constitutes the universe” - André Jolivet.

Only for the Flute alone he has composed no less than eleven pieces, ten of them being organized in two cycles. Five Incantations, five Ascéses composed in 1967 and the sixth Incantation composed independently in 1937, its title announcing the influence of symbolism: “For the image to become a symbol”. And, of course, it is the flute that takes on the main role in several of his chamber music works as well, such as “Chant de Linos”, “Sonata”, “Fantasy-Caprice for flute and piano” or “Sonatina for flute and clarinette”.

André Jolivet composed only two concertante pieces for flute, both dedicated to Jean-Pierre Rampal. A Concerto for flute and string orchestra” (1949) that was commissioned by the French government and a Suite en Concert (1965). The latter one was even subtitled by the composer as a “second concerto for flute” even though the solo flute is only accompanied by a group of four percussionists. This idea was initially commissioned by Jean-Pierre Rampal who as a concerto for flute and symphony orchestra!

At the end of the Second World War, Jolivet aspired to make a musical synthesis between the avant-garde and classicism. His preponderant wish to address with his music both intellectuals and a broader audience can be even more understood by the fact that he was mobilized in 1939 and has experienced the horrors of war ; especially during the battle of Gien where he lost several of his comrades under the German and Italian fire.

Concerto for flute and strings is probably one of the best examples of this period since it consists of two movements, both divided into slower and faster part. It opens with a slow, profound movement and its melodic richness brings us at its climax to the bustling scherzo, full of energy, character and lightness. Further on, magnificent phrases at the beginning of the second movement are conducted by the strings and only punctuated like an echo by the soloist. The last part of the concerto imposes itself almost violently, with the flute cutting off the orchestra and pursuing a combat of virtuosity which finishes at the very end with a spectacular unison.

In the Suite en Concert, the composer returns to his original idea that has been the guideline throughout his life: the music is magic! One can find the presence of wild, incantatory aspects, pivot notes, ostinatos, the use of chanted and/or complex rhythms, sound contrasts (air sounds of flute being juxtaposed to sound shocks without definite pitch of percussions) and a tendency to extend slurs over beats or even encompass several bars, which creates an illusion of a spontaneous outline composed of very precise rhythms. One can equally appreciate his passion for numerology, given the fact that his favorite number, the number 5, structures the entire score: 5 instrumentalists, pentatonic scale, the time signature of 5/4 or even the tempi indicated by the composer, of which the sum or the difference of the numbers given is equal to 5 (crotchet = 104 or 72).

In the end, four movements of the Suite en Concert form a very coherent cycle which is quite similar to the musical form of the same name from the Baroque period, and at the same time constitute an original piece which offers to the flute new possibilities of expression other than the dreamy poetical atmosphere to which the flute repertoire was up until then too often confined.

Finally, let us rethink the words that André Jolivet addressed to Jean-Pierre Rampal after his disappointment of not having a piece with a grand symphony orchestra: “You’ll see, it will be wild!”

I am glad to be able to present the collection of concertante pieces for flute written by these two major composers of the twentieth century edited in parallel for the first time on CD.

José-Daniel Castellon

(2019) Martin & Jolivet: Works for Flute & Orchestra - CD 1818

One being Swiss, the other one French, both have traveled throughout the twentieth century without really knowing each other, nevertheless they have shared an extraordinary amount of similarities.

Even though Frank Martin was 15 years older, they have both perished only one month apart at the end of 1974 and have therefore lived in parallel for almost the whole twentieth century. In the same manner, both received a solid musical education at first and later on seen their parents were opposed to their aspirations in making a living as musicians and therefore obliging their sons to choose, at first, an alternative profession to satisfy their families demands.

Both composers display in their music a great deal of mysticism or even fervent faith, which is frankly Christian with Martin and much more esoteric when it comes to Jolivet who was passionate about several thesis of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin.

They have expressed their spirituality in numerous works that were in terms of form quite conventional for their time (Oratorio, Cantata, Requiem Mass...). However, they have found a way to express it in much more unexpected musical forms, such as Frank Martin’s Sonata da Chiesa to which we will come back later, or Incantations written in 1936, which Jolivet wrote for the Flute alone and whose mystical dimension cannot be missed by anyone nowadays.

From a purely musical point of view, either of the two composers have found themselves entirely submerged into any of the so-called avant-garde movements that were predominant in the first half of the twentieth century. Without ignoring the fact that they have both used certain aspects of serialism, they have never completely renounced the concept of tonality and even though they have always stayed attached to the importance of melody, each of them has eventually found their own musical voice that cannot be reduced to any form of neoclassicism. Nonetheless, when considering the incantatory, wild or even violent aspects of André Jolivet’s music, one could consider that he has introduced the concept of Primitivism, if ever this movement even existed in the musical sphere.

As most flutists, I am particularly keen on Frank Martin’s music and even more so for André Jolivet’s who has enriched our repertoire. Even though both wrote marvelous pieces for our instrument, their individual approach towards it is quite different.

Even though Frank Martin was married to a flutist (Maria Martin) for a major part of his life, he has composed only few works where the flute is brought to the foreground. His Ballade has nonetheless become one of the most frequently performed works for flute. This masterpiece begins with an extremely expressive first movement, full of tension and anguish, while the second movement is fast, rhythmical and virtuosic (fireworks was the word critic once used to flatter my interpretation!). The historical value of the Ballade is worth mentioning as well since it was written for the Geneva International Music Competition in 1939, a year that can easily describe the gloomy and anguished atmosphere of the piece.

The Sonata da Chiesa, less famous, was originally conceived in 1938 for viola d’amore and organ. Shortly after, Frank Martin finalized the first arrangement for flute and organ, dedicated to his wife Maria, Victor Desarzens arranged the piece for flute and strings in 1958.

Victor Desarzens being a immense admirer of Frank Martin, found the energy and resources to give the first performance of the work with the Lausanne Chamber Orchestra in the middle of the Second World War. During three decades of service as the music director of Lausanne’s principal orchestra, he programmed 37 performances of Frank Martin’s works (more than those of Robert Schumann and as much as those of Franz Schubert!). Throughout their fruitful collaboration, both men became great friends.

Even though Desarzens loved the Ballade, he considered it a bit too short to be presented alone and therefore concieved his arrangement of Sonata da Chiesa in order to be able to perform both pieces consecutively. The “premiere” of this version took place the 18th of January 1959 with the flutist Marianne Clément being accompanied by the Lausanne Chamber Orchestra, led by its principal conductor. Frank Martin was indeed very pleased with the performance. The sound of a string orchestra enables a true contrast between the soloist and the accompaniment and brings to the score a new energy and breath. And lastly, the new arrangement now enabled more possibilites of execution, given the fact that organ is not present in all concert halls.

By contrast, the flute plays a central role in the catalog of André Jolivet’s works. For him, it is an instrument unlike any other: “The flute is close to nature, animated by the breath which is the vehicle of psychism and the emanation of the most profound being. It is a prime example of a musical instrument since it is essentially composed of a pierced hollow tube. Thanks to its simplicity it enables musicians to express their most profound feelings. It is therefore, besides the human voice, the most natural and the most ancient musical instrument. I think that the flute is the best means to communicate the feelings that connect us not only to our peers or any beings that have lived on the Earth, but to the ensemble of the forces that constitutes the universe” - André Jolivet.

Only for the Flute alone he has composed no less than eleven pieces, ten of them being organized in two cycles. Five Incantations, five Ascéses composed in 1967 and the sixth Incantation composed independently in 1937, its title announcing the influence of symbolism: “For the image to become a symbol”. And, of course, it is the flute that takes on the main role in several of his chamber music works as well, such as “Chant de Linos”, “Sonata”, “Fantasy-Caprice for flute and piano” or “Sonatina for flute and clarinette”.

André Jolivet composed only two concertante pieces for flute, both dedicated to Jean-Pierre Rampal. A Concerto for flute and string orchestra” (1949) that was commissioned by the French government and a Suite en Concert (1965). The latter one was even subtitled by the composer as a “second concerto for flute” even though the solo flute is only accompanied by a group of four percussionists. This idea was initially commissioned by Jean-Pierre Rampal who as a concerto for flute and symphony orchestra!

At the end of the Second World War, Jolivet aspired to make a musical synthesis between the avant-garde and classicism. His preponderant wish to address with his music both intellectuals and a broader audience can be even more understood by the fact that he was mobilized in 1939 and has experienced the horrors of war ; especially during the battle of Gien where he lost several of his comrades under the German and Italian fire.

Concerto for flute and strings is probably one of the best examples of this period since it consists of two movements, both divided into slower and faster part. It opens with a slow, profound movement and its melodic richness brings us at its climax to the bustling scherzo, full of energy, character and lightness. Further on, magnificent phrases at the beginning of the second movement are conducted by the strings and only punctuated like an echo by the soloist. The last part of the concerto imposes itself almost violently, with the flute cutting off the orchestra and pursuing a combat of virtuosity which finishes at the very end with a spectacular unison.

In the Suite en Concert, the composer returns to his original idea that has been the guideline throughout his life: the music is magic! One can find the presence of wild, incantatory aspects, pivot notes, ostinatos, the use of chanted and/or complex rhythms, sound contrasts (air sounds of flute being juxtaposed to sound shocks without definite pitch of percussions) and a tendency to extend slurs over beats or even encompass several bars, which creates an illusion of a spontaneous outline composed of very precise rhythms. One can equally appreciate his passion for numerology, given the fact that his favorite number, the number 5, structures the entire score: 5 instrumentalists, pentatonic scale, the time signature of 5/4 or even the tempi indicated by the composer, of which the sum or the difference of the numbers given is equal to 5 (crotchet = 104 or 72).

In the end, four movements of the Suite en Concert form a very coherent cycle which is quite similar to the musical form of the same name from the Baroque period, and at the same time constitute an original piece which offers to the flute new possibilities of expression other than the dreamy poetical atmosphere to which the flute repertoire was up until then too often confined.

Finally, let us rethink the words that André Jolivet addressed to Jean-Pierre Rampal after his disappointment of not having a piece with a grand symphony orchestra: “You’ll see, it will be wild!”

I am glad to be able to present the collection of concertante pieces for flute written by these two major composers of the twentieth century edited in parallel for the first time on CD.

José-Daniel Castellon

Return to the album | Read the booklet | Composer(s): André Jolivet | Main Artist: José-Daniel Castellon