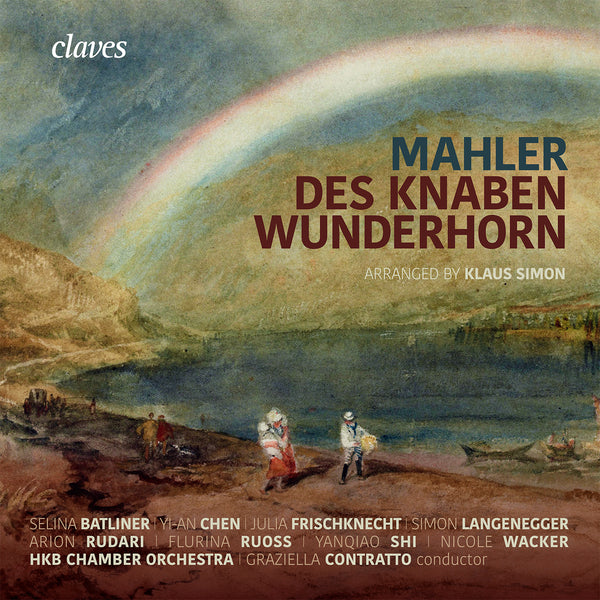

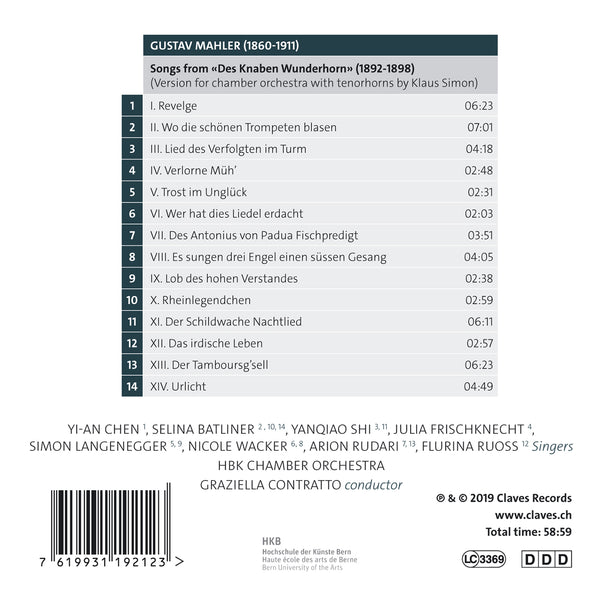

(2019) Mahler: Des Knaben Wunderhorn

Kategorie(n): Operngesang Orchester Repertoire

Hauptkomponist: Gustav Mahler

Orchester: HKB Chamber Orchestra

Dirigent: Graziella Contratto

CD-Set: 1

Katalog Nr.:

CD 1921

Freigabe: 22.03.2019

EAN/UPC: 7619931192123

Dieses Album ist jetzt neu aufgelegt worden. Bestellen Sie es jetzt zum Sonderpreis vor.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

Dieses Album ist noch nicht veröffentlicht worden. Bestellen Sie es jetzt vor.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

CHF 18.50

Inklusive MwSt. für die Schweiz und die EU

Kostenloser Versand

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

Inklusive MwSt. für die Schweiz und die EU

Kostenloser Versand

Dieses Album ist jetzt neu aufgelegt worden. Bestellen Sie es jetzt zum Sonderpreis vor.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

This album has not been released yet.

Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

SPOTIFY

(Verbinden Sie sich mit Ihrem Konto und aktualisieren die Seite, um das komplette Album zu hören)

MAHLER: DES KNABEN WUNDERHORN

What devilment is in them, bound up with the deepest mysticism! Everything is turned on its head, causality has completely ceased to apply !

(Gustav Mahler in a letter to Ludwig Karpath in 1905, writing about the Wunderhorn poems)

Fish that speak and donkeys as judges; deserters, phantom drummers, cheeky angels – but also wild, flirty country girls and macho guardsmen, even the Lord God himself: The Wunderhorn songs of Gustav Mahler are populated by a highly original, heterogeneous set of characters. What could be their common factor, apart from their typical Mahlerian tone? The answer is to be found some 90 years before these songs were composed. In 1805, under the collective title “The boy’s magic horn. Old German songs”, the two German Romantic poets Achim von Arnim und Clemens Brentano began publishing these and many other texts. They conceived their collection as a conscious revival of folk nature poetry and as offering a mirror to the “Riches of our whole people (and) its own inner, living art”, as von Arnim wrote. But these texts also reflect the (early) Romantic delight in the primordial, unspoilt and elemental.

At that time, folk poetry was regarded as an anti-Enlightenment guarantor of beauty and truth in art. Soon after the first Wunderhorn texts were published, however, the two editors were criticised for their interventions in the texts, which went far beyond what might be expected of mere collectors. They seemed to have encroached all too willingly on the natural formal language of the originals (though even the Brothers Grimm also heavily “adjusted” the texts of the fairy tales they collected and published…). Trying to find originality while at the same time subjecting their originals to manipulation was obviously not considered a contradiction in terms by these early Romantics …

The arrangement of an arrangement of an arrangement …

In the eponymous orchestral songs by Gustav Mahler, who from 1892 onwards busied himself for almost ten years with the literary and compositional possibilities of the Wunderhorn texts, we can observe a fascinating approach that shines a light on issues of artistic intervention: “They are boulders that everyone can shape into what he will”, is how he supposedly described his own approach to the “originals” in conversation with Natalie Bauer-Lechner. For this composer, the Wunderhorn texts were one component of his compositional process of sketching and shaping his music. Indeed, his practice of recycling (and “upcycling”) went so far that we speak of Mahler’s first four symphonies as his Wunderhorn symphonies, in which concrete, extended quotations and even whole songs bring vocal music and the symphonic into a close, fraternal relationship. We find whole symphony movements based on Wunderhorn texts (such as Urlicht, Es sungen drei Engel, Das himmlische Leben etc.), and often – as, for example, in Revelge – Mahler composed a song as a kind of follow-up to a symphony. In another letter, he wrote that “nothing less than the first movement of my Third [Symphony] must serve as a study for the rhythm of this song”.

Judging from his general reading habits, Mahler possessed an impressive literary sensibility. So it is not easy to explain his enthusiasm for folk poetry. He was a passionate, constant reader, though his preferences suggest that he was conservative in his literary leanings. His library included philosophical essays, the complete works of Goethe and Shakespeare, much by Jean Paul, Cervantes, Laurence Sterne, Charles Dickens, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, then all the Greek tragedies and a few contemporary poets from his circle of friends. The fact that he also had space for all the volumes of the science reference book Brehm’s Animal Life seems at first astonishing, but not so much, the more one thinks about it …

Tradition is sloppiness (Gustav Mahler)

If we look at the list of singers who gave the first performances of these songs, we can see that “Gustl” did not just work with established artists such as Anna von Mildenburg, whom he affectionately addressed – as quoted above – as his “Schaferl” (literally “little sheep”, though in connotation more along the lines of “lambkin”). His preferred performers also included much younger singers such as the baritone Anton Moser and the soprano Selma Kurz (who also had an affair with Mahler that almost culminated in matrimony). Kurz performed the intimate songs Wo die schönen Trompeten blasen and Das irdische Leben under Mahler in Vienna in 1900 when she was just 26 years old – which in fact corresponds to the average age of the singers on the present recording. The Wunderhorn songs, with their wonderful texts, provided the vocal students of the HBK with a welcome opportunity to situate their voices within the intoxicating, purring, chattering, commenting context of an orchestra, but without having to cope with the pressure of the large-scale orchestration of the originals.

The specifically vocal freshness of these young singers in their timbre and interpretation, and in their dialogue with the chamber group, would probably have delighted Mahler (given the reports of his strong antipathy to falsely understood tradition). The transparency of Simon’s arrangements, the vigour of the vocal colours and – who knows? – the fact that these young professionals are not yet “jaded”, perhaps means that their interpretation of these songs of the “folk” is in fact close to the old, Romantic ideal of the natural and the true. In this sense, this world-première recording is also an experiment that at the same time mischievously yet profoundly invites our listening expectations to adapt to new climes.

(Translated from German by Chris Walton)

Artist website: www.graziellacontratto.com

Orchestra website: www.hkb-musik.ch

What devilment is in them, bound up with the deepest mysticism! Everything is turned on its head, causality has completely ceased to apply !

(Gustav Mahler in a letter to Ludwig Karpath in 1905, writing about the Wunderhorn poems)

Fish that speak and donkeys as judges; deserters, phantom drummers, cheeky angels – but also wild, flirty country girls and macho guardsmen, even the Lord God himself: The Wunderhorn songs of Gustav Mahler are populated by a highly original, heterogeneous set of characters. What could be their common factor, apart from their typical Mahlerian tone? The answer is to be found some 90 years before these songs were composed. In 1805, under the collective title “The boy’s magic horn. Old German songs”, the two German Romantic poets Achim von Arnim und Clemens Brentano began publishing these and many other texts. They conceived their collection as a conscious revival of folk nature poetry and as offering a mirror to the “Riches of our whole people (and) its own inner, living art”, as von Arnim wrote. But these texts also reflect the (early) Romantic delight in the primordial, unspoilt and elemental.

At that time, folk poetry was regarded as an anti-Enlightenment guarantor of beauty and truth in art. Soon after the first Wunderhorn texts were published, however, the two editors were criticised for their interventions in the texts, which went far beyond what might be expected of mere collectors. They seemed to have encroached all too willingly on the natural formal language of the originals (though even the Brothers Grimm also heavily “adjusted” the texts of the fairy tales they collected and published…). Trying to find originality while at the same time subjecting their originals to manipulation was obviously not considered a contradiction in terms by these early Romantics …

The arrangement of an arrangement of an arrangement …

In the eponymous orchestral songs by Gustav Mahler, who from 1892 onwards busied himself for almost ten years with the literary and compositional possibilities of the Wunderhorn texts, we can observe a fascinating approach that shines a light on issues of artistic intervention: “They are boulders that everyone can shape into what he will”, is how he supposedly described his own approach to the “originals” in conversation with Natalie Bauer-Lechner. For this composer, the Wunderhorn texts were one component of his compositional process of sketching and shaping his music. Indeed, his practice of recycling (and “upcycling”) went so far that we speak of Mahler’s first four symphonies as his Wunderhorn symphonies, in which concrete, extended quotations and even whole songs bring vocal music and the symphonic into a close, fraternal relationship. We find whole symphony movements based on Wunderhorn texts (such as Urlicht, Es sungen drei Engel, Das himmlische Leben etc.), and often – as, for example, in Revelge – Mahler composed a song as a kind of follow-up to a symphony. In another letter, he wrote that “nothing less than the first movement of my Third [Symphony] must serve as a study for the rhythm of this song”.

Judging from his general reading habits, Mahler possessed an impressive literary sensibility. So it is not easy to explain his enthusiasm for folk poetry. He was a passionate, constant reader, though his preferences suggest that he was conservative in his literary leanings. His library included philosophical essays, the complete works of Goethe and Shakespeare, much by Jean Paul, Cervantes, Laurence Sterne, Charles Dickens, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, then all the Greek tragedies and a few contemporary poets from his circle of friends. The fact that he also had space for all the volumes of the science reference book Brehm’s Animal Life seems at first astonishing, but not so much, the more one thinks about it …

Tradition is sloppiness (Gustav Mahler)

If we look at the list of singers who gave the first performances of these songs, we can see that “Gustl” did not just work with established artists such as Anna von Mildenburg, whom he affectionately addressed – as quoted above – as his “Schaferl” (literally “little sheep”, though in connotation more along the lines of “lambkin”). His preferred performers also included much younger singers such as the baritone Anton Moser and the soprano Selma Kurz (who also had an affair with Mahler that almost culminated in matrimony). Kurz performed the intimate songs Wo die schönen Trompeten blasen and Das irdische Leben under Mahler in Vienna in 1900 when she was just 26 years old – which in fact corresponds to the average age of the singers on the present recording. The Wunderhorn songs, with their wonderful texts, provided the vocal students of the HBK with a welcome opportunity to situate their voices within the intoxicating, purring, chattering, commenting context of an orchestra, but without having to cope with the pressure of the large-scale orchestration of the originals.

The specifically vocal freshness of these young singers in their timbre and interpretation, and in their dialogue with the chamber group, would probably have delighted Mahler (given the reports of his strong antipathy to falsely understood tradition). The transparency of Simon’s arrangements, the vigour of the vocal colours and – who knows? – the fact that these young professionals are not yet “jaded”, perhaps means that their interpretation of these songs of the “folk” is in fact close to the old, Romantic ideal of the natural and the true. In this sense, this world-première recording is also an experiment that at the same time mischievously yet profoundly invites our listening expectations to adapt to new climes.

(Translated from German by Chris Walton)

Artist website: www.graziellacontratto.com

Orchestra website: www.hkb-musik.ch

Return to the album | Read the booklet | Composer(s): Gustav Mahler | Main Artist: Graziella Contratto