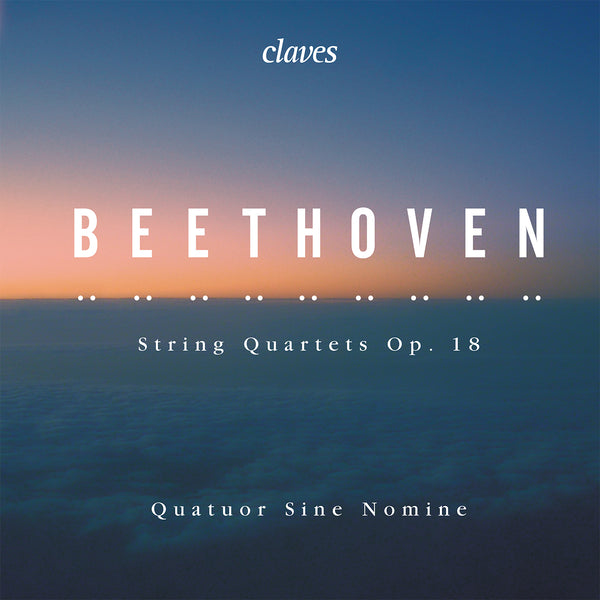

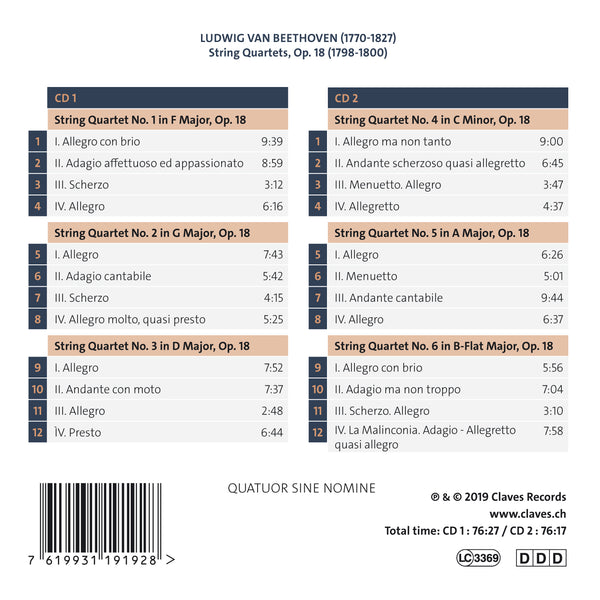

(2019) Beethoven: String Quartets, Op. 18

Category(ies): Chamber

Instrument(s): Cello Viola Violin

Main Composer: Ludwig van Beethoven

CD set: 2

Catalog N°:

CD 1919/20

Release: 06.09.2019

EAN/UPC: 7619931191928

This album is now on repressing. Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 24.00

This album is no longer available on CD.

This album has not been released yet. Pre-order it from now.

CHF 24.00

This album is no longer available on CD.

CHF 24.00

VAT included for Switzerland & UE

Free shipping

This album is no longer available on CD.

VAT included for Switzerland & UE

Free shipping

This album is now on repressing. Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 24.00

This album is no longer available on CD.

This album has not been released yet.

Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 24.00

This album is no longer available on CD.

CHF 24.00

This album is no longer available on CD.

BEETHOVEN: STRING QUARTETS, OP. 18

THE EMANCIPATION QUARTETS

November 1792. With a grant from the Prince-elector of Cologne and an invitation from Joseph Haydn to come and study with him, young Beethoven arrived in Vienna. At that time, there could be no better place for a musician to make a mark. The capital of the Habsburg Empire concentrated within its walls the finest authors of the Classical period, which was in its heyday. Though composition was not totally ignored, those first few years were primarily dedicated to the study and development of his concert career. His virtuosity rapidly secured him pride of place in the salons, where his interpretation of the Preludes and Fugues of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier was much appreciated.

Haydn’s departure for England in 1794 meant the end of the grant allocated to the “student” by the Prince-elector. Should he go back to Bonn? Beethoven never even considered it. Over two years, he had made enough friends to envisage an “independent” future quite serenely. His talent won over a few of the capital’s most prominent patrons, who were willing to pay for the services of the pianist for private evenings – and were later to be associated with the advent of his masterpieces. Although he was still to continue playing for a while longer – outshining the greatest virtuosos of his time in contests most dear to the Viennese -, he was increasingly focusing his energy on composition.

It was the end of the 18th century, and he was testing all sorts of genres with great brio, appearing to the audience not only as the worthy descendant of Haydn and Mozart, but also as the forerunner of a new expressive form – indeed a new music. “He commandeers our ears, but not our hearts, reason for which he will never be a Mozart for us”, wrote a critic at the end of a concert in 1796. A comment that says it all on the shock that his music could cause, even that which followed (on paper at least) straight from the classical lineage: the six Quartets op.18 (1798-1800) that concern us here are part of this, as does the “Pathétique” Sonata (1798), the Septet op. 20 (1799), or even the 1st Symphony (1800).

We know that Beethoven received a commission for a first String Quartet in 1795 already from one of the greatest Viennese patrons of the time, Count Anton Georg Apponyi, for whom Haydn had composed his opus 71 et 74 and who had just subscribed to purchasing six copies of his Trios op. 1. For unknown reasons, the process did not go through. Was Beethoven not yet confident enough to rival with the masterpieces of his mentor Haydn and those of Mozart who had just died? However, it was only delayed to later. Three years hence, another illustrious patron came knocking at his door: Prince Franz Joseph Maximilian von Lobkowitz, who made a double commission, both to the pupil and master. Far from recoiling, Beethoven threw himself passionately into the adventure. He was 28 years old and took the order as a challenge, as the opportunity to emancipate himself from his “tutor” in full daylight. The challenge was met: even before being published in 1801 by Tranquillo Mollo (under the French title « Six Quatuors pour deux violons, alto et violoncelle composés et dédiés à son Altesse Monseigneur le prince régnant de Lobkowitz par Louis van Beethoven » [Six Quartets for two violins, viola and ‘cello composed and dedicated to His Highness Prince von Lobkowitz by Ludwig van Beethoven]), the gems of this opus 18 met with great success, whereas Haydn “stalled” and could finally only deliver two quartets (opus 77) in 1802.

As is often the case, the order of publication does not correspond to the order of composition; it was in fact chosen by Beethoven himself, as underlying stylistic “manifests”. As mentioned by Elisabeth Brisson in her excellent Guide de la musique de Beethoven (Fayard, 2005), “Beethoven put the second Quartet (in the order of composition) in first place so as to show off immediately his principles of composition, favouring the initial motif and the work on this motif: this choice implicitly meant that he assumed responsibility for the novelty of his writing and that he was about to offer as many new solutions as quartets to the problems of the composition of such works. Similarly, he put in final place a Quartet that was introducing a new principle of tension.”

To summarise, the opus 18 Quartets were written in the following order: n° 3, 1, 2 (first group completed between the end of autumn 1798 and May 1799, resulting in an initial down payment of 200 Gulden to Beethoven), n° 5 (July-August 1799), 4 (summer-autumn 1799), 6 (between April and summer 1800). The collection was submitted to Prince Lobkowitz in October 1800 and resulted in a second payment of 200 Gulden. As for the first performances, we only have a trace of that of the Third Quartet (in D Major), played privately in the Prince’s salons by an ensemble led by violinist Karl Amenda, a dear friend of Beethoven’s.

Like the Second and Third, the First Quartet (in F Major) was seriously reworked before its submission to the Prince. Beethoven mentioned this in a letter addressed to Amenda on 1st July 1801: “Take care not to share my quartet with anyone, as I have reworked it a lot, considering I only now know how to write quartets correctly, as you will notice when you get them.” We also know, thanks to Amenda, that Beethoven was inspired by the tomb scene of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet for the contours of the slow movement, scene that tells of the heartbreaking separation of the two lovers: a statement confirmed by these verses found (in French) by the Coda on a draft sheet: “Il prend le tombeau / désespoir / il se tue / les derniers soupirs.” (He takes the tomb / despair / he kills himself / the final gasps).

The Second Quartet (in G Major) was nicknamed Komplimentierquartett (literally “Curtsey Quartet”) with reference to its gallant style evoking the aristocracy balls. The Fourth Quartet perfectly summarises the state of mind that Beethoven found himself in when delivering his first quartets to the public: both dependent on the past (certain passages still dated from Bonn) and conscious of the new voice that inhabited him, embodied by a key signature in C Minor, which was to become emblematic of the future dramatic masterpieces to be, such as the “Pathétique” Sonata. Whereas the Second evoked Haydn, the Fifth Quartet (in A Major) is an explicit homage to his other great model, Mozart, and more particularly to his Quartet n° 18 in A Major K. 464. We know from his pupil Czerny that Beethoven copied large passages of the score and apparently exclaimed, while doing so: “This is what I call a work !” Lastly, the Sixth Quartet (in B flat Major) is singled out by a Finale opening onto a poignant Adagio named “La Malinconia” (melancholy) … difficult to be more explicit !

QUATUOR SINE NOMINE

Patrick Genet & François Gottraux, violins

Hans Egidi, viola

Marc Jaermann, cello

Having distinguished itself at the Evian competition in 1985 and at the Borciani competition in Reggio Emilia in 1987, the Quatuor Sine Nomine, established in Lausanne, leads an international career, performing in some of the greatest venues in Europe (Wigmore Hall, Concertgebouw) and in the United States (Carnegie Hall).

The Quartet was deeply influenced by personalities such as Rose Dumur Hemmerling, to whom it owes its passion and love for the great tradition of the quartet, as well as the Melos Quartet and composer Henri Dutilleux, whom it met whilst recording his work Ainsi la Nuit (Erato), a particularly enriching experience. The life of the ensemble is enhanced through regular collaborations with other musicians. Close links have been established with quartets, such as the Vogler Quartet and the Carmina Quartet, as well as soloists Claire Désert, François Guye, Marie-Pierre Langlamet, Pascal Moraguès and Michel Portal.

The Quatuor Sine Nomine performs a vast repertoire, ranging from Haydn to the 21st century. Its repertoire also includes less known works such as the Enesco octet and contemporary creations especially dedicated to the ensemble, as were Swiss composer William Blank’s three quartets, published in 2016 by Genuin. Its wide-ranging discography includes great classics, such as the complete Schubert (Cascavelle) and the complete Brahms (Claves), the Arriaga quartets and the works of Turina (Claves), but also Furtwängler’s piano quintets (Timpani) and those of Goldmark (CPO). After the release of Beethoven’s middle quartets, the cycle of his six quartets op.18 is released in 2019 by Claves, upon the occasion of the composer’s 250th Anniversary.

In addition to its activity within the Quartet, each member leads an intense teaching career at the Lausanne and Geneva Universities of Music. The Quartet has also assumed the artistic direction of the Orchestre des Jeunes de la Suisse Romande since 2012. The ensemble founded the Sine Nomine Festival in 2001 and has been its artistic director since its creation.

In 2016, the Quatuor Sine Nomine was awarded the « Prix culturel » by the Fondation Leenaards.

THE EMANCIPATION QUARTETS

November 1792. With a grant from the Prince-elector of Cologne and an invitation from Joseph Haydn to come and study with him, young Beethoven arrived in Vienna. At that time, there could be no better place for a musician to make a mark. The capital of the Habsburg Empire concentrated within its walls the finest authors of the Classical period, which was in its heyday. Though composition was not totally ignored, those first few years were primarily dedicated to the study and development of his concert career. His virtuosity rapidly secured him pride of place in the salons, where his interpretation of the Preludes and Fugues of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier was much appreciated.

Haydn’s departure for England in 1794 meant the end of the grant allocated to the “student” by the Prince-elector. Should he go back to Bonn? Beethoven never even considered it. Over two years, he had made enough friends to envisage an “independent” future quite serenely. His talent won over a few of the capital’s most prominent patrons, who were willing to pay for the services of the pianist for private evenings – and were later to be associated with the advent of his masterpieces. Although he was still to continue playing for a while longer – outshining the greatest virtuosos of his time in contests most dear to the Viennese -, he was increasingly focusing his energy on composition.

It was the end of the 18th century, and he was testing all sorts of genres with great brio, appearing to the audience not only as the worthy descendant of Haydn and Mozart, but also as the forerunner of a new expressive form – indeed a new music. “He commandeers our ears, but not our hearts, reason for which he will never be a Mozart for us”, wrote a critic at the end of a concert in 1796. A comment that says it all on the shock that his music could cause, even that which followed (on paper at least) straight from the classical lineage: the six Quartets op.18 (1798-1800) that concern us here are part of this, as does the “Pathétique” Sonata (1798), the Septet op. 20 (1799), or even the 1st Symphony (1800).

We know that Beethoven received a commission for a first String Quartet in 1795 already from one of the greatest Viennese patrons of the time, Count Anton Georg Apponyi, for whom Haydn had composed his opus 71 et 74 and who had just subscribed to purchasing six copies of his Trios op. 1. For unknown reasons, the process did not go through. Was Beethoven not yet confident enough to rival with the masterpieces of his mentor Haydn and those of Mozart who had just died? However, it was only delayed to later. Three years hence, another illustrious patron came knocking at his door: Prince Franz Joseph Maximilian von Lobkowitz, who made a double commission, both to the pupil and master. Far from recoiling, Beethoven threw himself passionately into the adventure. He was 28 years old and took the order as a challenge, as the opportunity to emancipate himself from his “tutor” in full daylight. The challenge was met: even before being published in 1801 by Tranquillo Mollo (under the French title « Six Quatuors pour deux violons, alto et violoncelle composés et dédiés à son Altesse Monseigneur le prince régnant de Lobkowitz par Louis van Beethoven » [Six Quartets for two violins, viola and ‘cello composed and dedicated to His Highness Prince von Lobkowitz by Ludwig van Beethoven]), the gems of this opus 18 met with great success, whereas Haydn “stalled” and could finally only deliver two quartets (opus 77) in 1802.

As is often the case, the order of publication does not correspond to the order of composition; it was in fact chosen by Beethoven himself, as underlying stylistic “manifests”. As mentioned by Elisabeth Brisson in her excellent Guide de la musique de Beethoven (Fayard, 2005), “Beethoven put the second Quartet (in the order of composition) in first place so as to show off immediately his principles of composition, favouring the initial motif and the work on this motif: this choice implicitly meant that he assumed responsibility for the novelty of his writing and that he was about to offer as many new solutions as quartets to the problems of the composition of such works. Similarly, he put in final place a Quartet that was introducing a new principle of tension.”

To summarise, the opus 18 Quartets were written in the following order: n° 3, 1, 2 (first group completed between the end of autumn 1798 and May 1799, resulting in an initial down payment of 200 Gulden to Beethoven), n° 5 (July-August 1799), 4 (summer-autumn 1799), 6 (between April and summer 1800). The collection was submitted to Prince Lobkowitz in October 1800 and resulted in a second payment of 200 Gulden. As for the first performances, we only have a trace of that of the Third Quartet (in D Major), played privately in the Prince’s salons by an ensemble led by violinist Karl Amenda, a dear friend of Beethoven’s.

Like the Second and Third, the First Quartet (in F Major) was seriously reworked before its submission to the Prince. Beethoven mentioned this in a letter addressed to Amenda on 1st July 1801: “Take care not to share my quartet with anyone, as I have reworked it a lot, considering I only now know how to write quartets correctly, as you will notice when you get them.” We also know, thanks to Amenda, that Beethoven was inspired by the tomb scene of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet for the contours of the slow movement, scene that tells of the heartbreaking separation of the two lovers: a statement confirmed by these verses found (in French) by the Coda on a draft sheet: “Il prend le tombeau / désespoir / il se tue / les derniers soupirs.” (He takes the tomb / despair / he kills himself / the final gasps).

The Second Quartet (in G Major) was nicknamed Komplimentierquartett (literally “Curtsey Quartet”) with reference to its gallant style evoking the aristocracy balls. The Fourth Quartet perfectly summarises the state of mind that Beethoven found himself in when delivering his first quartets to the public: both dependent on the past (certain passages still dated from Bonn) and conscious of the new voice that inhabited him, embodied by a key signature in C Minor, which was to become emblematic of the future dramatic masterpieces to be, such as the “Pathétique” Sonata. Whereas the Second evoked Haydn, the Fifth Quartet (in A Major) is an explicit homage to his other great model, Mozart, and more particularly to his Quartet n° 18 in A Major K. 464. We know from his pupil Czerny that Beethoven copied large passages of the score and apparently exclaimed, while doing so: “This is what I call a work !” Lastly, the Sixth Quartet (in B flat Major) is singled out by a Finale opening onto a poignant Adagio named “La Malinconia” (melancholy) … difficult to be more explicit !

QUATUOR SINE NOMINE

Patrick Genet & François Gottraux, violins

Hans Egidi, viola

Marc Jaermann, cello

Having distinguished itself at the Evian competition in 1985 and at the Borciani competition in Reggio Emilia in 1987, the Quatuor Sine Nomine, established in Lausanne, leads an international career, performing in some of the greatest venues in Europe (Wigmore Hall, Concertgebouw) and in the United States (Carnegie Hall).

The Quartet was deeply influenced by personalities such as Rose Dumur Hemmerling, to whom it owes its passion and love for the great tradition of the quartet, as well as the Melos Quartet and composer Henri Dutilleux, whom it met whilst recording his work Ainsi la Nuit (Erato), a particularly enriching experience. The life of the ensemble is enhanced through regular collaborations with other musicians. Close links have been established with quartets, such as the Vogler Quartet and the Carmina Quartet, as well as soloists Claire Désert, François Guye, Marie-Pierre Langlamet, Pascal Moraguès and Michel Portal.

The Quatuor Sine Nomine performs a vast repertoire, ranging from Haydn to the 21st century. Its repertoire also includes less known works such as the Enesco octet and contemporary creations especially dedicated to the ensemble, as were Swiss composer William Blank’s three quartets, published in 2016 by Genuin. Its wide-ranging discography includes great classics, such as the complete Schubert (Cascavelle) and the complete Brahms (Claves), the Arriaga quartets and the works of Turina (Claves), but also Furtwängler’s piano quintets (Timpani) and those of Goldmark (CPO). After the release of Beethoven’s middle quartets, the cycle of his six quartets op.18 is released in 2019 by Claves, upon the occasion of the composer’s 250th Anniversary.

In addition to its activity within the Quartet, each member leads an intense teaching career at the Lausanne and Geneva Universities of Music. The Quartet has also assumed the artistic direction of the Orchestre des Jeunes de la Suisse Romande since 2012. The ensemble founded the Sine Nomine Festival in 2001 and has been its artistic director since its creation.

In 2016, the Quatuor Sine Nomine was awarded the « Prix culturel » by the Fondation Leenaards.

Return to the album | Read the booklet | Composer(s): Ludwig van Beethoven | Main Artist: Quatuor Sine Nomine