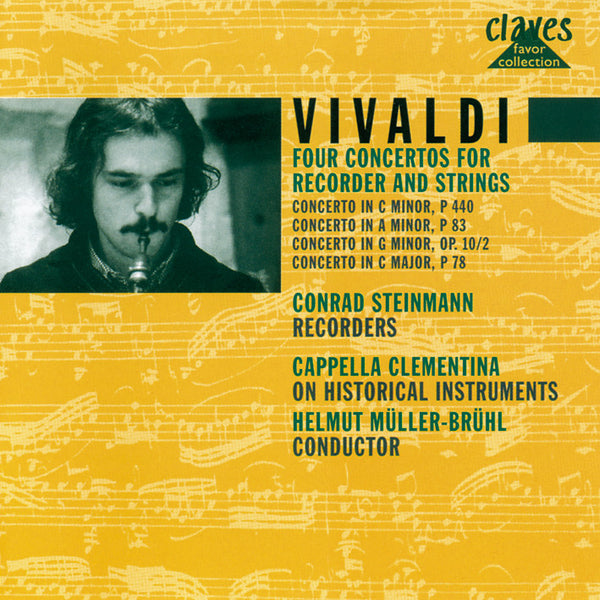

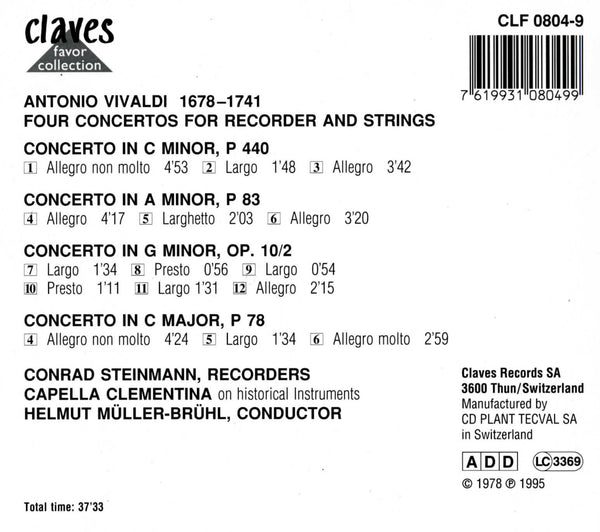

(1978) Vivaldi/ Flute Concertos

CD set: 1

Catalog N°:

CLF 804-9

Release: 1995

EAN/UPC: 7619931080499

This album is now on repressing. Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

This album has not been released yet. Pre-order it from now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

CHF 18.50

VAT included for Switzerland & UE

Free shipping

This album is no longer available on CD.

VAT included for Switzerland & UE

Free shipping

This album is now on repressing. Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

This album has not been released yet.

Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

VIVALDI/ FLUTE CONCERTOS

In 1700 the term flauto was generally understood to mean a recorder – specially a treble recorder, if no further details were given. (In England at the same time the expression used was “common flute”.) By 1750, however, the abbreviated and – by 1978 standards – imprecise word flauto had come to mean the transverse flute, or what is now the familiar silver (or silver-plate) Boehm Flute. Both examples confirm, through common acceptance of a single meaning for an indefinite term, how widely used each instrument must have been.

Vivaldi, however, used precise terminology to distinguish between the recorder (flauto and flautino) and the flute (flauto traverso). Nor was the difference one of nomenclature only: Vivaldi made a clear distinction between the two in the texture and structure of his work. Thus, while he deliberately made use of the flute’s advantages in cantabile playing, a wealth of dynamic shadings, it was in his pieces for recorder that an almost excessive element of virtuosity comes to the fore.

Virtuosity in this context did not have a negative connotation, but revealed Vivaldi’s intimate knowledge of the possibilities inherent in the recorder. This does not disguise the fact that the occurrence of extremely rapid broken chords in Vivaldi’s music owed more to his violin technique than to any thought for the sorely taxed fingers and tongue of the recorder player!

Listening to these four concertos, one is struck by the singularity of the G minor concerto, “La Notte”, on account of the demands made on the soloist. The explanation must be that the far less-exposed solo line was intended for the flute, and was never meant originally for the recorder. It is no coincidence, either, that as in the rest of the flute concertos in Vivaldi’s Op. 10, the compass never goes below that of the recorder.

Thoughts of how to increase sales of his music (by having both recorder and flute able to play the same pieces) came as easily to Vivaldi as to his contemporary (and even more, modern) publishers. This also helps to provide a rough date for the pieces here: the three recorder works were probably written soon after 1723, and certainly before Op. 10 was printed in 1729/30 – see the Introduction.

Vivaldi wrote six recorder concertos in all, three each for flauto and flautino. The exact meaning of flautino has long been a mystery. Musicologists have tried to prove, often by questionable arguments, that it must have been a flageolet – an instrument, however, which was never mentioned at the time. Although in different places the compass extends below the recorder’s range (the first tutti in the first movement of the concerto in C major, the introductory tutti in the third movement of the A minor concerto, and one solo passage in the A minor), these are in fact misleading. Except for the solo passage, the range of the soloist is f” to f””, corresponding exactly to that of a sopranino recorder. One is even more in the dark, trying to imagine how the flauto / flautino of Vivaldi’s Venice must have sounded.

I believe, nevertheless, that there are analogies with German instruments of the same period (hence the copies of instruments by J.C. Denner of Nüremberg, used in this recording). As with range, the demands of both German and Italian music of the late Baroque require the use of recorders of a diminished size that sound well and even in all ranges.

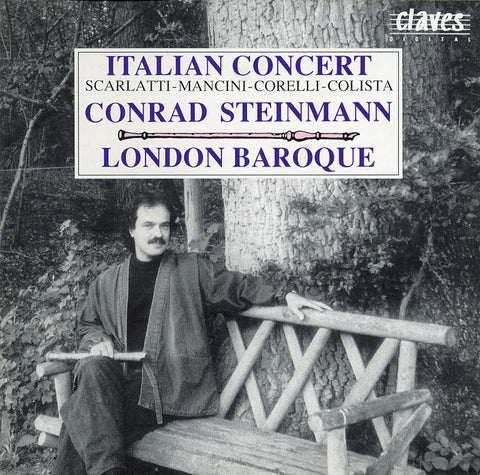

Conrad Steinmann

(1978) Vivaldi/ Flute Concertos - CLF 804-9

In 1700 the term flauto was generally understood to mean a recorder – specially a treble recorder, if no further details were given. (In England at the same time the expression used was “common flute”.) By 1750, however, the abbreviated and – by 1978 standards – imprecise word flauto had come to mean the transverse flute, or what is now the familiar silver (or silver-plate) Boehm Flute. Both examples confirm, through common acceptance of a single meaning for an indefinite term, how widely used each instrument must have been.

Vivaldi, however, used precise terminology to distinguish between the recorder (flauto and flautino) and the flute (flauto traverso). Nor was the difference one of nomenclature only: Vivaldi made a clear distinction between the two in the texture and structure of his work. Thus, while he deliberately made use of the flute’s advantages in cantabile playing, a wealth of dynamic shadings, it was in his pieces for recorder that an almost excessive element of virtuosity comes to the fore.

Virtuosity in this context did not have a negative connotation, but revealed Vivaldi’s intimate knowledge of the possibilities inherent in the recorder. This does not disguise the fact that the occurrence of extremely rapid broken chords in Vivaldi’s music owed more to his violin technique than to any thought for the sorely taxed fingers and tongue of the recorder player!

Listening to these four concertos, one is struck by the singularity of the G minor concerto, “La Notte”, on account of the demands made on the soloist. The explanation must be that the far less-exposed solo line was intended for the flute, and was never meant originally for the recorder. It is no coincidence, either, that as in the rest of the flute concertos in Vivaldi’s Op. 10, the compass never goes below that of the recorder.

Thoughts of how to increase sales of his music (by having both recorder and flute able to play the same pieces) came as easily to Vivaldi as to his contemporary (and even more, modern) publishers. This also helps to provide a rough date for the pieces here: the three recorder works were probably written soon after 1723, and certainly before Op. 10 was printed in 1729/30 – see the Introduction.

Vivaldi wrote six recorder concertos in all, three each for flauto and flautino. The exact meaning of flautino has long been a mystery. Musicologists have tried to prove, often by questionable arguments, that it must have been a flageolet – an instrument, however, which was never mentioned at the time. Although in different places the compass extends below the recorder’s range (the first tutti in the first movement of the concerto in C major, the introductory tutti in the third movement of the A minor concerto, and one solo passage in the A minor), these are in fact misleading. Except for the solo passage, the range of the soloist is f” to f””, corresponding exactly to that of a sopranino recorder. One is even more in the dark, trying to imagine how the flauto / flautino of Vivaldi’s Venice must have sounded.

I believe, nevertheless, that there are analogies with German instruments of the same period (hence the copies of instruments by J.C. Denner of Nüremberg, used in this recording). As with range, the demands of both German and Italian music of the late Baroque require the use of recorders of a diminished size that sound well and even in all ranges.

Conrad Steinmann

Return to the album | Main Artist: Conrad Steinmann