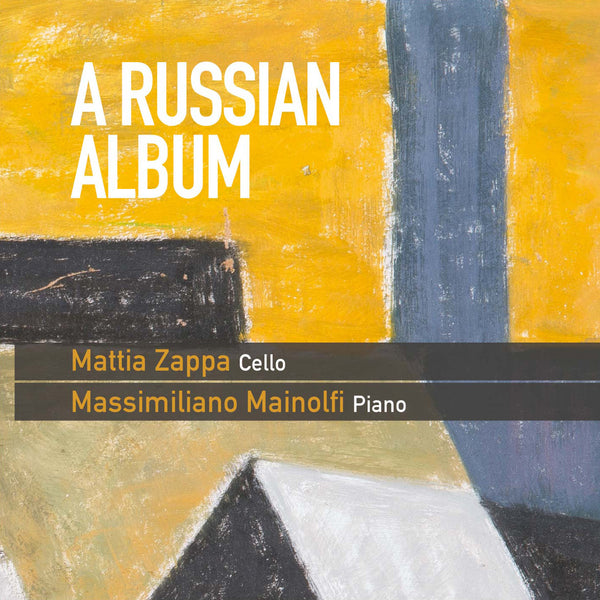

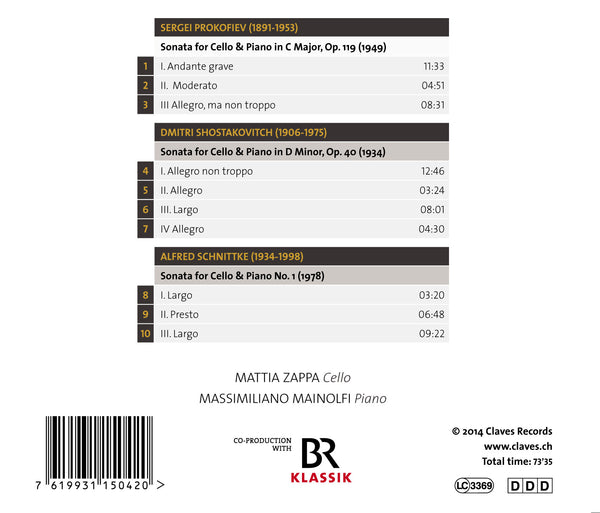

(2015) A Russian Album, Duo Zappa-Mainolfi, Cello & Piano

Category(ies): Chamber Piano

Instrument(s): Cello Piano

Main Composer: Sergei Prokofiev

CD set: 1

Catalog N°:

CD 1504

Release: 01.02.2015

EAN/UPC: 7619931150420

- UPC: 889176090745

This album is now on repressing. Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

This album has not been released yet. Pre-order it from now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

CHF 18.50

VAT included for Switzerland & UE

Free shipping

This album is no longer available on CD.

VAT included for Switzerland & UE

Free shipping

This album is now on repressing. Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

This album has not been released yet.

Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

A RUSSIAN ALBUM, DUO ZAPPA-MAINOLFI, CELLO & PIANO

Shostakovich’s Cello Sonata in d minor, op. 40 (1934) was in one of the first expressions of this trend. Shostakovich bows to ‘papa’ Haydn more than once in the traditional four-movement cycle comprised of a sonata Allegro, a happy-go-lucky Scherzo, a meditative Largo and a cheeky rondo Finale. A contemporary of the “classical turn” in Soviet aesthetics, the Sonata also marked a turn in Shostakovich’s personal style from the defiantly angular musical stance that matched the experimentalist spirit of the Soviet 1920s to the accessible, affable musical language that became privileged by the state in the Stalinist 1930s. The genre of cello sonata suited particularly well to the task: striking a balance between the distinctive, voice-like sound of the cello and the time-honored musical form could be readily perceived as conveying the desired synthesis of personal utterance and social sanction. Just as readily, however, the ambivalent genre can be interpreted as underscoring tension rather than concord. Shostakovich’s Sonata provides evidence for either construal. In the opening Allegro, the lyrical current, gentle at first, swells inordinately by the movement’s middle. But it is tamed in a succession of lulling passages in the recapitulation. The clumsily compulsive Scherzo has more affinity with Mahlerian irony than with Haydnesque wit. Unlike Mahler, however, here Shostakovich never really ventures beyond the limits of the stylistically acceptable, aiming more for sheer exuberance than sharp ridicule. The lyrical line continues in the brooding Largo that draws on tuneful Baroque adagios, but also on Shostakovich’s own oeuvre: the dark, searching sound evokes the somber music of the Siberian exile from his then-recent Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. The whimsical, kaleidoscopic Finale balances on the very edge of irreverence, yet even here all attempts at transgression are offset by the obligatory return of the old-fashioned refrain. It may seem now as though all possible flights of passion in this Sonata are met with some form of disciplining, but the lyrical verve never fully subsides. Quite the opposite: the continual equilibrium of excess and moderation lends the Sonata the general air of playfulness and romantic mischief. Whether that air refracted the sparkle of the composer’s extramarital affair that burgeoned at the time of the Sonata’s composition, or represented his effort to fit the newly privileged neoclassical mold – or both! – very few of Shostakovich’s later works reach the same level of poise and buoyancy.

Prokofiev’s Cello Sonata in C major op. 119 (1949), written for the 22-year old Mstislav Rostropovich and dedicated to Prokofiev’s composer-friend Levon Atovmyan, hails from the final years of the Stalin era, marked by the launching of the Cold War and the subsequent renewal of the anti-Western conservatism in Soviet aesthetics. Reproached by the Party in 1948 for allegedly transgressing the laws of accessibility in his still-dissonant works, Prokofiev sought to reclaim respect (as well as recover from what would ultimately prove to be an irremediable blow) by producing placid, melodious music that drew on traditional genres and styles. This, however, did not mean that he stopped being his unique composerly self. The three movements of his Sonata expectedly engage classical forms, but the ways in which they muster the now-mandatory feelings of unity and optimism are unmistakably Prokofiev’s. The composer seems determined to prove his collectivist allegiance by adding the ever-broader historical – and also specifically Russian – pedigree to the already storied genre. The principal themes of the opening Andante grave evoke musical styles ranging from a Mozartian serenade to a Russian protyazhnaya (a drawn-out folk song, here much reminiscent of the mezzo-soprano lament from Prokofiev’s Alexander Nevsky). The development conjures up something even more legendary: a Baroque fugato and a bylina, Russian medieval narrative epic, complete with quasi-improvisatory flourishes and a zither-like accompaniment. The middle movement, Moderato, is a sort of Gavotte, a hoppy 18th-century dance that Prokofiev had already explored in 1917 in his “Classical” symphony. Warm lyricism and jovial valiance predominate in the final Allegro ma non troppo, invoking the romantic enchantments of Prokofiev’s earlier Romeo and Juliet. In the coda, the spacious first theme from the Andante reappears in a halo of virtuosic jubilatory passages, generating a compelling sonic image of apotheosis. A fruit of political precautiousness, but also of Prokofiev’s inspired friendship with Rostropovich, this Sonata continues to dazzle performers and listeners alike.

Schnittke’s Cello Sonata no. 1 (1978), dedicated to (and written for) the cellist Natalya Gutman, is a product of the late-Soviet period now known as “stagnation”: an era of political status quo, relative social stability and inveterate aesthetic conservatism. Schnittke was one of the casualties, but also in some respects beneficiaries, of that age. His Cello Sonata, just like its “polystylistic” contemporaries his Concerto Grosso no. 1 and “Moz-Art a la Haydn,” wrestles with reputable musical styles and genres by pitting irreverence against veneration. The opening Largo starts off the game: its first bars seem to promise a properly Baroque piece for solo cello, only to startle the listener with the launch of the piano part after some 90 seconds of the cello’s soliloquy. The oscillation between the solo and the duet brings about other kinds of wavering: those between major and minor, chromaticism and diatonicism, allusion and abstraction. The eerie Largo meets its own counterpart in the rhythmic, intensely material Presto, which begins as a fast devilish chase, perhaps inspired by Schnittke’s recent forays into film music. The chase, however, eventually disintegrates, weakened by the Presto’s disjunct middle section in which once-meaningful musical acts appear reduced to their most basic constituents: a soft sigh, a stray waltzing ‘oom-pah-pah,’ a neurotic trill. The earlier delicate oscillation returns in the final Largo along with some already-heard sounds. Unexpectedly (and thus well within Schnittke’s system of paradox), this movement is all about integration. Here the clashing miscellany of the previous movements congeals into an expressive monologue, the cello forming one single voice with the piano in terms of both style and sentiment. Schnittke’s motley, soft-lens neoclassicism may be of a distinctly post-modernist vintage, but it also reflects the deadly seriousness with which generations of creative artists in the USSR clutched on to their calling. In the vein of both Shostakovich and Prokofiev, this composer, even at his most arcane, privileges expressivity and sonic richness overcynicism and abstract play of sounds.

Anna Nisnevich

The three Russian cello sonatas on this CD offer three strikingly different takes on the genre – all, however, stemming from the tradition of what can be called Soviet neoclassicism.

Shostakovich’s Cello Sonata in d minor, op. 40 (1934) was in one of the first expressions of this trend. Shostakovich bows to ‘papa’ Haydn more than once in the traditional four-movement cycle comprised of a sonata Allegro, a happy-go-lucky Scherzo, a meditative Largo and a cheeky rondo Finale. A contemporary of the “classical turn” in Soviet aesthetics, the Sonata also marked a turn in Shostakovich’s personal style from the defiantly angular musical stance that matched the experimentalist spirit of the Soviet 1920s to the accessible, affable musical language that became privileged by the state in the Stalinist 1930s. The genre of cello sonata suited particularly well to the task: striking a balance between the distinctive, voice-like sound of the cello and the time-honored musical form could be readily perceived as conveying the desired synthesis of personal utterance and social sanction. Just as readily, however, the ambivalent genre can be interpreted as underscoring tension rather than concord. Shostakovich’s Sonata provides evidence for either construal. In the opening Allegro, the lyrical current, gentle at first, swells inordinately by the movement’s middle. But it is tamed in a succession of lulling passages in the recapitulation. The clumsily compulsive Scherzo has more affinity with Mahlerian irony than with Haydnesque wit. Unlike Mahler, however, here Shostakovich never really ventures beyond the limits of the stylistically acceptable, aiming more for sheer exuberance than sharp ridicule. The lyrical line continues in the brooding Largo that draws on tuneful Baroque adagios, but also on Shostakovich’s own oeuvre: the dark, searching sound evokes the somber music of the Siberian exile from his then-recent Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. The whimsical, kaleidoscopic Finale balances on the very edge of irreverence, yet even here all attempts at transgression are offset by the obligatory return of the old-fashioned refrain. It may seem now as though all possible flights of passion in this Sonata are met with some form of disciplining, but the lyrical verve never fully subsides. Quite the opposite: the continual equilibrium of excess and moderation lends the Sonata the general air of playfulness and romantic mischief. Whether that air refracted the sparkle of the composer’s extramarital affair that burgeoned at the time of the Sonata’s composition, or represented his effort to fit the newly privileged neoclassical mold – or both! – very few of Shostakovich’s later works reach the same level of poise and buoyancy.

Prokofiev’s Cello Sonata in C major op. 119 (1949), written for the 22-year old Mstislav Rostropovich and dedicated to Prokofiev’s composer-friend Levon Atovmyan, hails from the final years of the Stalin era, marked by the launching of the Cold War and the subsequent renewal of the anti-Western conservatism in Soviet aesthetics. Reproached by the Party in 1948 for allegedly transgressing the laws of accessibility in his still-dissonant works, Prokofiev sought to reclaim respect (as well as recover from what would ultimately prove to be an irremediable blow) by producing placid, melodious music that drew on traditional genres and styles. This, however, did not mean that he stopped being his unique composerly self. The three movements of his Sonata expectedly engage classical forms, but the ways in which they muster the now-mandatory feelings of unity and optimism are unmistakably Prokofiev’s. The composer seems determined to prove his collectivist allegiance by adding the ever-broader historical – and also specifically Russian – pedigree to the already storied genre. The principal themes of the opening Andante grave evoke musical styles ranging from a Mozartian serenade to a Russian protyazhnaya (a drawn-out folk song, here much reminiscent of the mezzo-soprano lament from Prokofiev’s Alexander Nevsky). The development conjures up something even more legendary: a Baroque fugato and a bylina, Russian medieval narrative epic, complete with quasi-improvisatory flourishes and a zither-like accompaniment. The middle movement, Moderato, is a sort of Gavotte, a hoppy 18th-century dance that Prokofiev had already explored in 1917 in his “Classical” symphony. Warm lyricism and jovial valiance predominate in the final Allegro ma non troppo, invoking the romantic enchantments of Prokofiev’s earlier Romeo and Juliet. In the coda, the spacious first theme from the Andante reappears in a halo of virtuosic jubilatory passages, generating a compelling sonic image of apotheosis. A fruit of political precautiousness, but also of Prokofiev’s inspired friendship with Rostropovich, this Sonata continues to dazzle performers and listeners alike.

Schnittke’s Cello Sonata no. 1 (1978), dedicated to (and written for) the cellist Natalya Gutman, is a product of the late-Soviet period now known as “stagnation”: an era of political status quo, relative social stability and inveterate aesthetic conservatism. Schnittke was one of the casualties, but also in some respects beneficiaries, of that age. His Cello Sonata, just like its “polystylistic” contemporaries his Concerto Grosso no. 1 and “Moz-Art a la Haydn,” wrestles with reputable musical styles and genres by pitting irreverence against veneration. The opening Largo starts off the game: its first bars seem to promise a properly Baroque piece for solo cello, only to startle the listener with the launch of the piano part after some 90 seconds of the cello’s soliloquy. The oscillation between the solo and the duet brings about other kinds of wavering: those between major and minor, chromaticism and diatonicism, allusion and abstraction. The eerie Largo meets its own counterpart in the rhythmic, intensely material Presto, which begins as a fast devilish chase, perhaps inspired by Schnittke’s recent forays into film music. The chase, however, eventually disintegrates, weakened by the Presto’s disjunct middle section in which once-meaningful musical acts appear reduced to their most basic constituents: a soft sigh, a stray waltzing ‘oom-pah-pah,’ a neurotic trill. The earlier delicate oscillation returns in the final Largo along with some already-heard sounds. Unexpectedly (and thus well within Schnittke’s system of paradox), this movement is all about integration. Here the clashing miscellany of the previous movements congeals into an expressive monologue, the cello forming one single voice with the piano in terms of both style and sentiment. Schnittke’s motley, soft-lens neoclassicism may be of a distinctly post-modernist vintage, but it also reflects the deadly seriousness with which generations of creative artists in the USSR clutched on to their calling. In the vein of both Shostakovich and Prokofiev, this composer, even at his most arcane, privileges expressivity and sonic richness overcynicism and abstract play of sounds.

Anna Nisnevich

Return to the album | Read the booklet | Composer(s): Sergei Prokofiev Alfred Schnittke | Main Artist: Duo Zappa Mainolfi