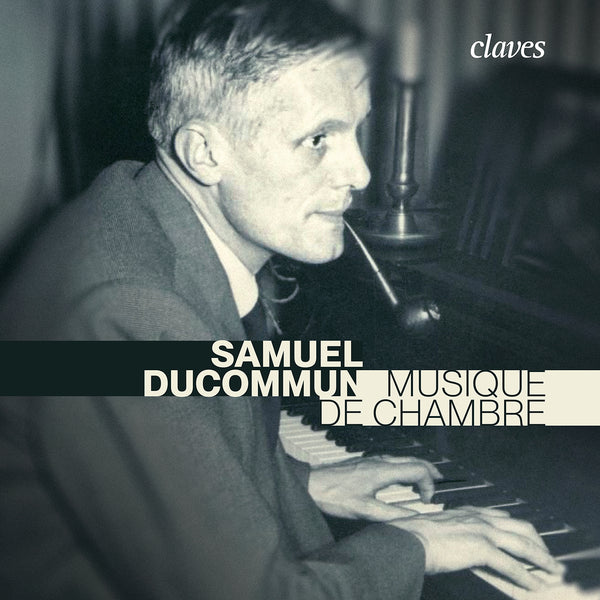

(2023) Samuel Ducommun: Musique de chambre

Category(ies): Chamber Piano

Instrument(s): Cello Flute Piano Violin

Main Composer: Samuel Ducommun

CD set: 1

Catalog N°:

CD 3071

Release: 15.09.2023

EAN/UPC: 7619931307121

This album is now on repressing. Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

This album has not been released yet. Pre-order it from now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

CHF 18.50

VAT included for Switzerland & UE

Free shipping

This album is no longer available on CD.

VAT included for Switzerland & UE

Free shipping

This album is now on repressing. Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

This album has not been released yet.

Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

SAMUEL DUCOMMUN: MUSIQUE DE CHAMBRE

Friendship and family

Both a singer as well as an inveterate music lover, the public prosecutor for the State of Neuchâtel Pierre Aubert also happens to be the author of one of the rare portraits of Samuel Ducommun (with perhaps the monography published at Infolio in 2014 by the undersigned...). It begins with this compelling assertion about this man’s relation to posterity: “Faulkner once said: It is my ambition to be, as a private individual, abolished and voided from history, leaving it markless, no refuse save the printed books (Joseph Leo Blotner, 1978, Selected letters of William Faulkner). Yet, a biography of more than a thousand pages was written about him. Samuel Ducommun appears to have been even more reserved than Faulkner. He never spoke about himself, didn’t have any personal ambition, not even to disappear from history, and even the destiny of his work, before and after his death, didn’t interest him”. Towards the end of his life he will state: “For a composer, the very fact of having accomplished his work, solving problems, managing to progress, seems to me the ultimate reward. The joy of a public performance of one’s creations is an added pleasure, but it isn’t imperative.” This form of extreme abnegation is Samuel Ducommun’s own business. And it must be respected. However, it needn’t prevent other people from paying close attention to his work: after all hadn’t Ducommun spent a good part of his life drawing his pupils’ attention (in his singing, organ tutoring and theory classes) to the innumerable treasures to be found in the history of music ? Perhaps, had he feared the disadvantage of comparisons... If such was the case, he was proved wrong. His inventory is made up of more than a hundred pieces of music of all types (with the exception of opera). It shows a steadfast vision, prompted just as much by his masters, as by his firm attachment to the Protestant cult. This powerful inner inspiration renders his art at once identifiable.

Opening doors

Is one in truth born with such creativity ? Samuel Ducommun will show his forceful resolve on the first day of summer in the ill-fated year of 1914, in Peseux, near Neuchâtel. His father, an accountant at the Suchard Factory, had been bringing up his two children on his own, ever since 1923 when his wife died: he made sure that “willingly or not” (according to Pierre Aubert) his children would become accomplished musicians, while making sure his son acquired a “real profession” at the same time! The Swiss institution for future teachers (Ecole Normale) offers an ideal combination, allowing space for artistic studies: Samuel Ducommun will thus become a schoolmaster, and he will never complain about his profession. To teach is to pass on knowledge opening doors, enabling pupils to come into their own, not so different from composing really, apart from the fact that the teacher is doing this “live”, on turf, so to speak. To teach is also creating bonds, sowing seeds of knowledge that might blossom years later: apart from his music still somewhat confidentially known, the testimonies of his charisma as a teacher are numerous, and without doubt prove to be the best consecration in regard to a man fully dedicated to his fellow being.

The organist

Samuel Ducommun is in good hands from the beginning. Enthralled with the organ at an early age – he sees Charles Faller’s feet, very active on the church gallery in Le Locle, Charles Faller who later will become his teacher – he studies under the guidance of Louis Kelterborn, and later is tutored by Faller, all the way to his Master achieved in 1938. Samuel Ducommun then goes to Paris and benefits from Marcel Dupré’s magnificent knowledge. He is taught theory by Charles Humbert and Paul Benner (whose masterpieces as well as those of Ducommun will soon be performed in concert halls). After Corcelles and Bienne, he settles down at the Neuchâtel Collegiate Church in 1942, where he will officiate for 45 years. So, along with his predecessor Albert Quinche who had taken up his post in 1902, one could say they both almost cover the entire century! One of his greatest achievements during that time is the creation in 1943 of an association, a forerunner in fact of the still very active “Société des Concerts de la Collegiale”, which will manage to raise the money in order to acquire a brand new organ unveiled in 1952 by Marcel Dupré himself!

An apple a day

Meanwhile Samuel Ducommun is an accomplished soloist in all of Switzerland as well as in the bordering countries, as he disliked travelling... Special attention is paid to 20th century music (including Swiss composers). He teaches the organ, harmony, analysis, counterpoint and composition at Neuchâtel Conservatory. And of course, he composes. His daughter Jacqueline, who died too soon in December 2021 after having championed his music all her life recalled: “He carried at all times a small notebook in which he’d jot down themes, ideas, chords, figured bass, or melodies, to be harmonised later by his students. Whenever a piece was in preparation, he’d withdraw into a world of his own, a world to which his family circle and set had but little access. He became absent-minded and unforthcoming. Yet, as soon as he’d return to his task, the score would fill in effortlessly as if the music piece had already been completed inside his head.” Despite the fact that several of his compositions are dedicated to specific musicians or happen to be commissioned work (Les Voix de la Forêt for example, written for 1964 Exposition Nationale, journée neuchâteloise) most however are totally spontaneous. He enjoyed saying: “An apple tree does not question why it produces apples.” So, in spite of the disappearance of the tree in 1987, Samuel Ducommun’s “apples” deserve to be savoured! The present record, supported by the Pantillon family – another great dynasty of musicians from Neuchâtel – is a living proof of this statement.

Composed in the Spring of 1949, Deux Pièces for cello and piano Op. 43 are premiered the following year, broadcast on Radio-Paris by the cellist André Levy and the composer himself at the piano. A much sought-after chamber music partner, friend of Charles Faller, Levy plays a pivotal role in the development of La Chaux-de-Fonds and Le Locle Conservatories. He is invited regularly (between 1948 and 1968) at the concerts given in Neuchâtel Collegiate Church, organised by Samuel Ducommun. Written shortly afterwards, Quatre Pièces brèves for cello and piano Op. 58, dedicated to Pablo Casals, will at last be played on May 25th 1972, during the Contemporary Music Concerts (CMC) in La Chaux-de-Fonds; Andrée Courvoisier and Cécile Pantillon (daughter of Georges- Louis) are the performers, and the composer presents his work himself. Recorded by Radio Suisse Romande, this piece of music is broadcast on March 23rd 1973, and once again on June 24th 1979, during a concert committed to “Swiss Composers”.

Written for flute, violin, viola, cello and piano, the Divertimento Op. 100 emanates from his affinities with the young musicians of his region, namely Ad Musicam Ensemble, whose members are the following: Charles Aeschlimann, Elisabeth Grimm, Christine Sörensen, François Hotz (his nephew and cello player who will be invited several times to perform at the Collegiate), and Olivier Sörensen. The creation takes place on October 3rd 1982 at the Art and History Museum of Neuchâtel at the occasion of its regular “Dimanches Musicaux”. The piece is given once again on January 31st 1984 for the 394th (!) hour of Contemporary Music at La Chaux-de-Fonds Conservatory; its coverage is done by the diligent Denise de Ceunynck for L’Impartial newspaper. She writes: “A first rate contemporary piece was given on Tuesday night [...] freely inspired by the Concerto Grosso, it accomplishes a sort of skills assessment of the composer’s former production. In this delightfully well- written piece, one finds a true synergy between dreams, imagination, logic of structure; one can note a mobility of rythms in the fugue forming the Allegro scherzando; the instumental color and many other details fully convinced the audience that this was indeed a radiant accomplishment. [...]”

1984 is the year of the Quatuor pour flûtes Op. 104, written as “a friendly tribute to the Quatuor de flûtes romand” (piccolo, flute, alto flute and bass flute). Let us savour the very emotional testimony given after the composer’s death, of Jean-Paul Haering, kingpin of the ensemble: “I met Samuel Ducommun during exams sessions at Neuchâtel and La Chaux-de-Fonds Conservatories. (...) The time we spent together after the exams enabled me to talk to him about the Quatuor de flûtes romand and also the scores that had been previously written for us by friends composers.

He spontaneously suggested that he could write a quartet piece for us, our ensemble having the piccolo, flute, alto and bass flute, which meant a very large range, which motivated him. Quite soon I received the score. During one of our rehearsals, Samuel Ducommun showed up in Neuchâtel to listen to the outcome of his work (and ours). He told us how pleased he was and declared “he had a field day composing that quartet.” Sadly, when we played the piece for the first time before an audience (on June 21st 1989), Samuel Ducommun was no longer alive.”

Once again there is a story of friendship in relation to the Sonatine pour violon et piano Op. 108, premiered in 1986 at the Lyceum-Club with violonist Jan Dobrzelewski, disciple of Ettore Brero (founder of Orchestre de Chambre de Neuchâtel, and dedicated performer of Ducommun’s creations ever since the fifties) and the pianist June Pantillon (wife of Georges- Henri [son of Georges-Louis], mother of Marc, Louis, Christophe, and Anne-Laure’s grandmother).

Antonin Scherrer

Translation Estelle Massy-Parramore

Artists

Anne-Laure Pantillon, flute

Theresa Wunderlin, flute

Aline Glasson, flute

Alba Luna Sanz, flute

Klara Flieder, violin

Johannes Flieder, alto

Christophe Pantillon, cello

Marc Pantillon, piano

REVIEWS

"Klangschön hören sich die Kompositionen von Samuel Ducommun (1914–1987) an. Der Organist und Musikpädagoge aus Neuchâtel hat ein reichhaltiges Werk hinterlassen, das zwar nicht vergessen, aber auch nicht sehr bekannt ist. Diese Auswahl an Kammermusik des findigen Brückenbauers zwischen französischem Impressionismus, Neoklassik und polytonaler Avantgarde offenbart ein besonderes Stück Schweizer Musikgeschichte." - Frank von Niederhäusern, September 2023

"This recording documents Samuel Ducommun’s chamber music. It covers the diversity in the composer’s chamber music oeuvre, his very personal and unique musical language in representative examples. More importantly, it keeps alive the memory of a composer who led a modest life and never made an effort to promote his music beyond a very small, private circle. [..]"

Friendship and family

Both a singer as well as an inveterate music lover, the public prosecutor for the State of Neuchâtel Pierre Aubert also happens to be the author of one of the rare portraits of Samuel Ducommun (with perhaps the monography published at Infolio in 2014 by the undersigned...). It begins with this compelling assertion about this man’s relation to posterity: “Faulkner once said: It is my ambition to be, as a private individual, abolished and voided from history, leaving it markless, no refuse save the printed books (Joseph Leo Blotner, 1978, Selected letters of William Faulkner). Yet, a biography of more than a thousand pages was written about him. Samuel Ducommun appears to have been even more reserved than Faulkner. He never spoke about himself, didn’t have any personal ambition, not even to disappear from history, and even the destiny of his work, before and after his death, didn’t interest him”. Towards the end of his life he will state: “For a composer, the very fact of having accomplished his work, solving problems, managing to progress, seems to me the ultimate reward. The joy of a public performance of one’s creations is an added pleasure, but it isn’t imperative.” This form of extreme abnegation is Samuel Ducommun’s own business. And it must be respected. However, it needn’t prevent other people from paying close attention to his work: after all hadn’t Ducommun spent a good part of his life drawing his pupils’ attention (in his singing, organ tutoring and theory classes) to the innumerable treasures to be found in the history of music ? Perhaps, had he feared the disadvantage of comparisons... If such was the case, he was proved wrong. His inventory is made up of more than a hundred pieces of music of all types (with the exception of opera). It shows a steadfast vision, prompted just as much by his masters, as by his firm attachment to the Protestant cult. This powerful inner inspiration renders his art at once identifiable.

Opening doors

Is one in truth born with such creativity ? Samuel Ducommun will show his forceful resolve on the first day of summer in the ill-fated year of 1914, in Peseux, near Neuchâtel. His father, an accountant at the Suchard Factory, had been bringing up his two children on his own, ever since 1923 when his wife died: he made sure that “willingly or not” (according to Pierre Aubert) his children would become accomplished musicians, while making sure his son acquired a “real profession” at the same time! The Swiss institution for future teachers (Ecole Normale) offers an ideal combination, allowing space for artistic studies: Samuel Ducommun will thus become a schoolmaster, and he will never complain about his profession. To teach is to pass on knowledge opening doors, enabling pupils to come into their own, not so different from composing really, apart from the fact that the teacher is doing this “live”, on turf, so to speak. To teach is also creating bonds, sowing seeds of knowledge that might blossom years later: apart from his music still somewhat confidentially known, the testimonies of his charisma as a teacher are numerous, and without doubt prove to be the best consecration in regard to a man fully dedicated to his fellow being.

The organist

Samuel Ducommun is in good hands from the beginning. Enthralled with the organ at an early age – he sees Charles Faller’s feet, very active on the church gallery in Le Locle, Charles Faller who later will become his teacher – he studies under the guidance of Louis Kelterborn, and later is tutored by Faller, all the way to his Master achieved in 1938. Samuel Ducommun then goes to Paris and benefits from Marcel Dupré’s magnificent knowledge. He is taught theory by Charles Humbert and Paul Benner (whose masterpieces as well as those of Ducommun will soon be performed in concert halls). After Corcelles and Bienne, he settles down at the Neuchâtel Collegiate Church in 1942, where he will officiate for 45 years. So, along with his predecessor Albert Quinche who had taken up his post in 1902, one could say they both almost cover the entire century! One of his greatest achievements during that time is the creation in 1943 of an association, a forerunner in fact of the still very active “Société des Concerts de la Collegiale”, which will manage to raise the money in order to acquire a brand new organ unveiled in 1952 by Marcel Dupré himself!

An apple a day

Meanwhile Samuel Ducommun is an accomplished soloist in all of Switzerland as well as in the bordering countries, as he disliked travelling... Special attention is paid to 20th century music (including Swiss composers). He teaches the organ, harmony, analysis, counterpoint and composition at Neuchâtel Conservatory. And of course, he composes. His daughter Jacqueline, who died too soon in December 2021 after having championed his music all her life recalled: “He carried at all times a small notebook in which he’d jot down themes, ideas, chords, figured bass, or melodies, to be harmonised later by his students. Whenever a piece was in preparation, he’d withdraw into a world of his own, a world to which his family circle and set had but little access. He became absent-minded and unforthcoming. Yet, as soon as he’d return to his task, the score would fill in effortlessly as if the music piece had already been completed inside his head.” Despite the fact that several of his compositions are dedicated to specific musicians or happen to be commissioned work (Les Voix de la Forêt for example, written for 1964 Exposition Nationale, journée neuchâteloise) most however are totally spontaneous. He enjoyed saying: “An apple tree does not question why it produces apples.” So, in spite of the disappearance of the tree in 1987, Samuel Ducommun’s “apples” deserve to be savoured! The present record, supported by the Pantillon family – another great dynasty of musicians from Neuchâtel – is a living proof of this statement.

Composed in the Spring of 1949, Deux Pièces for cello and piano Op. 43 are premiered the following year, broadcast on Radio-Paris by the cellist André Levy and the composer himself at the piano. A much sought-after chamber music partner, friend of Charles Faller, Levy plays a pivotal role in the development of La Chaux-de-Fonds and Le Locle Conservatories. He is invited regularly (between 1948 and 1968) at the concerts given in Neuchâtel Collegiate Church, organised by Samuel Ducommun. Written shortly afterwards, Quatre Pièces brèves for cello and piano Op. 58, dedicated to Pablo Casals, will at last be played on May 25th 1972, during the Contemporary Music Concerts (CMC) in La Chaux-de-Fonds; Andrée Courvoisier and Cécile Pantillon (daughter of Georges- Louis) are the performers, and the composer presents his work himself. Recorded by Radio Suisse Romande, this piece of music is broadcast on March 23rd 1973, and once again on June 24th 1979, during a concert committed to “Swiss Composers”.

Written for flute, violin, viola, cello and piano, the Divertimento Op. 100 emanates from his affinities with the young musicians of his region, namely Ad Musicam Ensemble, whose members are the following: Charles Aeschlimann, Elisabeth Grimm, Christine Sörensen, François Hotz (his nephew and cello player who will be invited several times to perform at the Collegiate), and Olivier Sörensen. The creation takes place on October 3rd 1982 at the Art and History Museum of Neuchâtel at the occasion of its regular “Dimanches Musicaux”. The piece is given once again on January 31st 1984 for the 394th (!) hour of Contemporary Music at La Chaux-de-Fonds Conservatory; its coverage is done by the diligent Denise de Ceunynck for L’Impartial newspaper. She writes: “A first rate contemporary piece was given on Tuesday night [...] freely inspired by the Concerto Grosso, it accomplishes a sort of skills assessment of the composer’s former production. In this delightfully well- written piece, one finds a true synergy between dreams, imagination, logic of structure; one can note a mobility of rythms in the fugue forming the Allegro scherzando; the instumental color and many other details fully convinced the audience that this was indeed a radiant accomplishment. [...]”

1984 is the year of the Quatuor pour flûtes Op. 104, written as “a friendly tribute to the Quatuor de flûtes romand” (piccolo, flute, alto flute and bass flute). Let us savour the very emotional testimony given after the composer’s death, of Jean-Paul Haering, kingpin of the ensemble: “I met Samuel Ducommun during exams sessions at Neuchâtel and La Chaux-de-Fonds Conservatories. (...) The time we spent together after the exams enabled me to talk to him about the Quatuor de flûtes romand and also the scores that had been previously written for us by friends composers.

He spontaneously suggested that he could write a quartet piece for us, our ensemble having the piccolo, flute, alto and bass flute, which meant a very large range, which motivated him. Quite soon I received the score. During one of our rehearsals, Samuel Ducommun showed up in Neuchâtel to listen to the outcome of his work (and ours). He told us how pleased he was and declared “he had a field day composing that quartet.” Sadly, when we played the piece for the first time before an audience (on June 21st 1989), Samuel Ducommun was no longer alive.”

Once again there is a story of friendship in relation to the Sonatine pour violon et piano Op. 108, premiered in 1986 at the Lyceum-Club with violonist Jan Dobrzelewski, disciple of Ettore Brero (founder of Orchestre de Chambre de Neuchâtel, and dedicated performer of Ducommun’s creations ever since the fifties) and the pianist June Pantillon (wife of Georges- Henri [son of Georges-Louis], mother of Marc, Louis, Christophe, and Anne-Laure’s grandmother).

Antonin Scherrer

Translation Estelle Massy-Parramore

Artists

Anne-Laure Pantillon, flute

Theresa Wunderlin, flute

Aline Glasson, flute

Alba Luna Sanz, flute

Klara Flieder, violin

Johannes Flieder, alto

Christophe Pantillon, cello

Marc Pantillon, piano

REVIEWS

"Klangschön hören sich die Kompositionen von Samuel Ducommun (1914–1987) an. Der Organist und Musikpädagoge aus Neuchâtel hat ein reichhaltiges Werk hinterlassen, das zwar nicht vergessen, aber auch nicht sehr bekannt ist. Diese Auswahl an Kammermusik des findigen Brückenbauers zwischen französischem Impressionismus, Neoklassik und polytonaler Avantgarde offenbart ein besonderes Stück Schweizer Musikgeschichte." - Frank von Niederhäusern, September 2023

"This recording documents Samuel Ducommun’s chamber music. It covers the diversity in the composer’s chamber music oeuvre, his very personal and unique musical language in representative examples. More importantly, it keeps alive the memory of a composer who led a modest life and never made an effort to promote his music beyond a very small, private circle. [..]"

Return to the album | Read the booklet | Composer(s): Samuel Ducommun | Main Artist: Marc Pantillon

STUDIO MASTER (HIGH-RESOLUTION AUDIO)

Aline Glasson

Alto

Amethys Design

Anne-Laure Pantillon

Cello

Chamber

Christophe Pantillon

Flute

High-resolution audio - Studio master quality

In stock

Johannes Flieder

Klara Flieder

Marc Pantillon - piano

New releases

Piano

Samuel Ducommun (1914-1987)

Sound engineer - Jean-Claude Gaberel

Theresa Wunderlin

Violin

World Premiere Recording

Aline Glasson

Alto

Amethys Design

Anne-Laure Pantillon

Cello

Chamber

Christophe Pantillon

Flute

High-resolution audio - Studio master quality

In stock

Johannes Flieder

Klara Flieder

Marc Pantillon - piano

New releases

Piano

Samuel Ducommun (1914-1987)

Sound engineer - Jean-Claude Gaberel

Theresa Wunderlin

Violin

World Premiere Recording