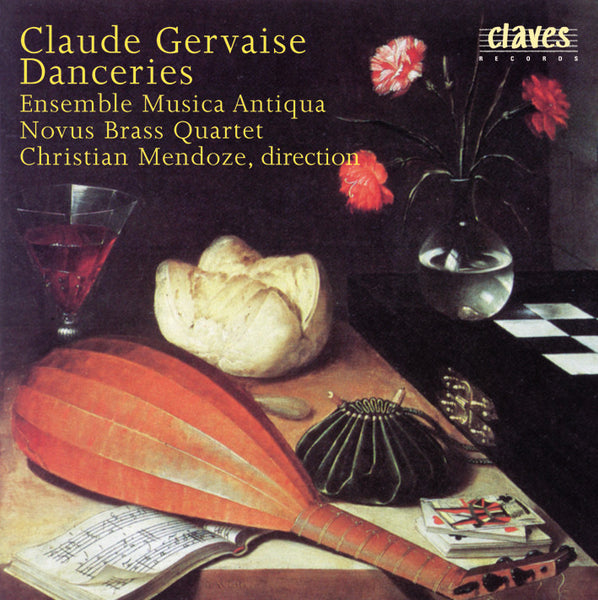

(1997) Claude Gervaise : Danceries (A quatre parties)

CD set: 1

Catalog N°:

CD 9616

EAN/UPC: 7619931961620

- UPC: 886788336483

This album is now on repressing. Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

This album has not been released yet. Pre-order it from now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

This album is no longer available on CD.

VAT included for Switzerland & UE

Free shipping

This album is now on repressing. Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

This album has not been released yet.

Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

This album is no longer available on CD.

NEW: Purchases are now made in the currency of your country. Change country here or at checkout

CLAUDE GERVAISE : DANCERIES (A QUATRE PARTIES

Alongside Italy's prolific but also highly inspired, sometimes to the point of grandiloquence, a less rhetorical but more playful musical genre was developing in France: the air de danse. The melodic theme of each dance was commonly called timbre. These airs appeared in a variety of forms, depending on the audience for which they were intended: sometimes they were called harmonized “danse de cour”, sometimes “dancerie” (the term used by Claude Gervaise). Where the term air de cour would spontaneously conjure up images of a staid dance to aristocratic music, we're more likely to hear a background of songs that ran through the streets, or courrantes, as they were called. André Verchaly has pointed out the popular origin of this term (vaudeville - city voices) and the name given to all sung airs, accompanied or unaccompanied. When heard in this way, these courtly airs lent themselves to the wishes of humanist poets, who were above all concerned with the clear intelligibility of their verses set to music. These simple, infinitely malleable tunes served their purpose marvelously.

In these dance tunes, you can always feel freshness and lightness, well-being and naturalness. The challenge of combining lightness and liveliness is always met; lightness is never superficial, and freshness is at the same time full of generosity. The reassuring gentleness and tenderness that emerge in the midst of the dances, often expressed by a lute solo, suffer no dead or weak moments. All in all, a kind of serene jubilation emanates from these instrumental pieces; the renaissance and humanist spirit was thus clearly bringing together the intellectual and artistic elite and the humbler social classes of the time.

Moralists were alarmed by this new fashion, yet these new dances were increasingly introduced into aristocratic and bourgeois entertainments. And so, little by little, the suite was organized, i.e., a stereotyped succession of these dances: for example, the pavane-gaillarde couple, a now-accepted and deemed harmonious alternation of a slow and a turbulent dance.

In these arrangements and pieces by Claude Gervaise, here is a new interpretation and orchestration, in which the bursts of brass, the rasgueados of the lute, the dense vibrations of the strings (violins, viola da gamba) and other inventions (in the classical sense of the word, “fantasy”) let us taste the flavors and charms of humanist freedom: the present interpretation strives to reproduce today the spirit of free, warm and generous inventiveness of humanist music. In this way, we can truly say that the new taste for early music has been definitively incorporated into our 20th-century culture.

Alongside Italy's prolific but also highly inspired, sometimes to the point of grandiloquence, a less rhetorical but more playful musical genre was developing in France: the air de danse. The melodic theme of each dance was commonly called timbre. These airs appeared in a variety of forms, depending on the audience for which they were intended: sometimes they were called harmonized “danse de cour”, sometimes “dancerie” (the term used by Claude Gervaise). Where the term air de cour would spontaneously conjure up images of a staid dance to aristocratic music, we're more likely to hear a background of songs that ran through the streets, or courrantes, as they were called. André Verchaly has pointed out the popular origin of this term (vaudeville - city voices) and the name given to all sung airs, accompanied or unaccompanied. When heard in this way, these courtly airs lent themselves to the wishes of humanist poets, who were above all concerned with the clear intelligibility of their verses set to music. These simple, infinitely malleable tunes served their purpose marvelously.

In these dance tunes, you can always feel freshness and lightness, well-being and naturalness. The challenge of combining lightness and liveliness is always met; lightness is never superficial, and freshness is at the same time full of generosity. The reassuring gentleness and tenderness that emerge in the midst of the dances, often expressed by a lute solo, suffer no dead or weak moments. All in all, a kind of serene jubilation emanates from these instrumental pieces; the renaissance and humanist spirit was thus clearly bringing together the intellectual and artistic elite and the humbler social classes of the time.

Moralists were alarmed by this new fashion, yet these new dances were increasingly introduced into aristocratic and bourgeois entertainments. And so, little by little, the suite was organized, i.e., a stereotyped succession of these dances: for example, the pavane-gaillarde couple, a now-accepted and deemed harmonious alternation of a slow and a turbulent dance.

In these arrangements and pieces by Claude Gervaise, here is a new interpretation and orchestration, in which the bursts of brass, the rasgueados of the lute, the dense vibrations of the strings (violins, viola da gamba) and other inventions (in the classical sense of the word, “fantasy”) let us taste the flavors and charms of humanist freedom: the present interpretation strives to reproduce today the spirit of free, warm and generous inventiveness of humanist music. In this way, we can truly say that the new taste for early music has been definitively incorporated into our 20th-century culture.

Return to the album | Main Artist: Christian Mendoze