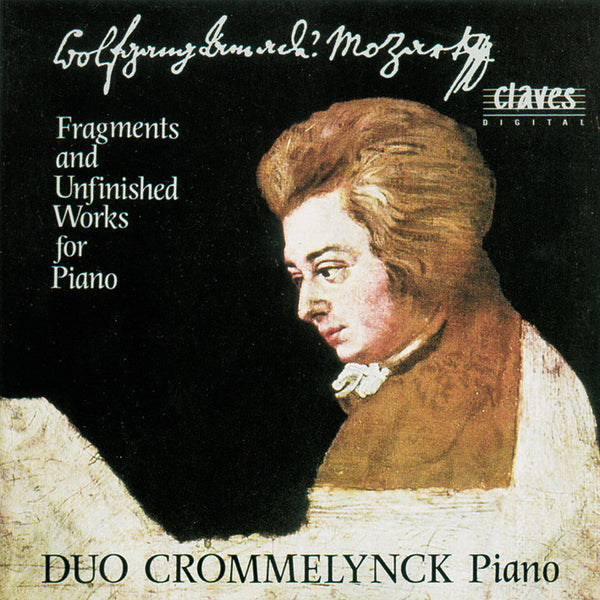

(1991) Fragments & Unfinished Works For Piano, Two Pianos & Piano Four Hands

Category(ies): Piano

Instrument(s): Piano

Main Composer: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

CD set: 1

Catalog N°:

CD 9109

Release: 1991

EAN/UPC: 7619931910925

- UPC: 829410609760

This album is now on repressing. Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

This album has not been released yet. Pre-order it from now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

CHF 18.50

VAT included for Switzerland & UE

Free shipping

This album is no longer available on CD.

VAT included for Switzerland & UE

Free shipping

This album is now on repressing. Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

This album has not been released yet.

Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

FRAGMENTS & UNFINISHED WORKS FOR PIANO, TWO PIANOS & PIANO FOUR HANDS

"Only someone who was flooded by inspiration could have composed so much in so short a life. Mozart's manuscripts, void of all signs of correction or variation, attest to the fact that he could even compose while chatting, e.g., about the ducks or the chickens."

When reading such descriptions one gains the impression that Mozart wrote his compositions in an unbroken stream and without error. Yes, Mozart started at the beginning of a work when composing. He also composed his operas working from the beginning to the end. That is certainly a different method of composition than Beethoven's, for example, who made numerous sketches, rewrote passages over and over again, experimented with the order of sections, etc. (One of the meanings of the verb to compose is to construct, and in this sense of the word it is Beethoven's compositional method which is perhaps the more primary.)

"Mozart liked to compose in the morning, from six or seven to around ten o'clock. As long as he wasn't under the pressure of having to meet a deadline, he usually didn't write a single note more after that. If, however, an idea suddenly came to him, then he immediately began to compose and there was no stopping him. Even when he was pulled away from the piano he would continue to compose while simultaneously speaking with his friends. Sometimes he would write uninterrupted for days and nights. At other times he didn't have the slightest desire to compose and would wait until just before a concert to complete a composition. Once he put off composing a commission from the court until the very last minute and didn't have the time to write out his own part. Emperor Joseph II did not oversee that Mozart's score was blank and asked him where his music was, upon which Mozart answered, simultaneously pointing to his head, here." (Stendhal)

Such episodes demonstrate the true dimensions of Mozart's unique genius. When inspired he could compose a work in a single sitting. It would be wrong, however, to claim that Mozart was infallible. Although his talents were extraordinary, almost divine, it should not be forgotten that he was human. Sometimes he noticed while composing that the piece that he was working on was not exactly that what he wanted, upon which he would immediately stop work on this composition. He forewent the work of correcting and preferred to wait for a new, 'heavenly' inspiration. Thus he never regretted abandoning an idea or leaving a composition unfinished. This stands in sharp contrast to a composer like Beethoven, who had conceived the famous melody to the last movement from his Ninth Symphony during his youth in Bonn, only to wait thirty years before finding the right place to employ it.

Mozart's compositional process was very 'simple;' he composed everything mentally. Writing was more the work of a copyist who merely had to bring the completed work onto paper. The speed with which Mozart wrote is legendary. He wrote, e.g., the overture to Don Giovanni on the evening before the premier. In order not to fall asleep while writing, he had his wife tell him stories from Aladin’s Lamp. When the copyist arrived the next morning the score had already been completed ... Although the truth of this anecdote has not been proven, the accuracy of the following story has: Mozart learned upon his arrival in Linz on October 30th, 1783, that he was expected to give a concert only four days later (on November 4th). Since he did not have the scores to any of his symphonies with him, he spontaneously decided to compose a new one. Within four days he had completed a new symphony (including writing out the parts for the individual instruments): the Linz Symphony, K. 425.

Many of Mozart's masterpieces were composed in this manner. Just as many works, however, remained unfinished, perhaps because Mozart didn't consider them perfect, or because he lost interest in them or because he wasn't motivated by the commission. Some of these unfinished works consist of just a few measures, some lack perhaps the development or the recapitulation, and others are almost complete. Mozart's genius is also to be found in these compositions, brilliant and captivating.

Each of these fragments and unfinished compositions, even the shortest, has its own particular background and story. Much more interesting than their history, however, is that which remains hidden in these works, their unfulfilled 'musical potential.' To conjecture about how Mozart might have continued or finished these compositions is a particularly entrancing pastime without end. The fragments and unfinished works for piano gathered on this recording contribute to a particularly personal and perpetually evolving image of Mozart insofar that one is continually confronted with the question: what might have been if ...

Mark Manion, adapted from Hiroshi Ishii

***

Duo Crommelynck

Duo Crommelynck has had an unparalleled career, and with their success they have brought a once forgotten phenomenon back into popularity: the piano duo and its extensive repertoire. Patrick Crommelynck studied with Stefan Askenase at the Brussels Conservatory, with Victor Metjanov at the Tchaikovsky Conservatory in Moscow and with Dieter Weber in Vienna. Taeko Kuwata studied with Kazuko Yasukawa at the Toho Academy in Tokyo and in Vienna with Bruno Seidlhofer and Dieter Weber, in whose class she met Patrick Crommelynck. In 1974 they joined forces to form a duo, embarking on a brilliant, international career. Their recordings have won numerous international awards.

The Duo Crommelynck's prodigious repertoire extends from the 18th century to contemporary compositions, some of which have been composed specifically for them. Included in their repertoire of over thirty programs are original works for piano duet as well as piano versions of major symphonic works.

"Only someone who was flooded by inspiration could have composed so much in so short a life. Mozart's manuscripts, void of all signs of correction or variation, attest to the fact that he could even compose while chatting, e.g., about the ducks or the chickens."

When reading such descriptions one gains the impression that Mozart wrote his compositions in an unbroken stream and without error. Yes, Mozart started at the beginning of a work when composing. He also composed his operas working from the beginning to the end. That is certainly a different method of composition than Beethoven's, for example, who made numerous sketches, rewrote passages over and over again, experimented with the order of sections, etc. (One of the meanings of the verb to compose is to construct, and in this sense of the word it is Beethoven's compositional method which is perhaps the more primary.)

"Mozart liked to compose in the morning, from six or seven to around ten o'clock. As long as he wasn't under the pressure of having to meet a deadline, he usually didn't write a single note more after that. If, however, an idea suddenly came to him, then he immediately began to compose and there was no stopping him. Even when he was pulled away from the piano he would continue to compose while simultaneously speaking with his friends. Sometimes he would write uninterrupted for days and nights. At other times he didn't have the slightest desire to compose and would wait until just before a concert to complete a composition. Once he put off composing a commission from the court until the very last minute and didn't have the time to write out his own part. Emperor Joseph II did not oversee that Mozart's score was blank and asked him where his music was, upon which Mozart answered, simultaneously pointing to his head, here." (Stendhal)

Such episodes demonstrate the true dimensions of Mozart's unique genius. When inspired he could compose a work in a single sitting. It would be wrong, however, to claim that Mozart was infallible. Although his talents were extraordinary, almost divine, it should not be forgotten that he was human. Sometimes he noticed while composing that the piece that he was working on was not exactly that what he wanted, upon which he would immediately stop work on this composition. He forewent the work of correcting and preferred to wait for a new, 'heavenly' inspiration. Thus he never regretted abandoning an idea or leaving a composition unfinished. This stands in sharp contrast to a composer like Beethoven, who had conceived the famous melody to the last movement from his Ninth Symphony during his youth in Bonn, only to wait thirty years before finding the right place to employ it.

Mozart's compositional process was very 'simple;' he composed everything mentally. Writing was more the work of a copyist who merely had to bring the completed work onto paper. The speed with which Mozart wrote is legendary. He wrote, e.g., the overture to Don Giovanni on the evening before the premier. In order not to fall asleep while writing, he had his wife tell him stories from Aladin’s Lamp. When the copyist arrived the next morning the score had already been completed ... Although the truth of this anecdote has not been proven, the accuracy of the following story has: Mozart learned upon his arrival in Linz on October 30th, 1783, that he was expected to give a concert only four days later (on November 4th). Since he did not have the scores to any of his symphonies with him, he spontaneously decided to compose a new one. Within four days he had completed a new symphony (including writing out the parts for the individual instruments): the Linz Symphony, K. 425.

Many of Mozart's masterpieces were composed in this manner. Just as many works, however, remained unfinished, perhaps because Mozart didn't consider them perfect, or because he lost interest in them or because he wasn't motivated by the commission. Some of these unfinished works consist of just a few measures, some lack perhaps the development or the recapitulation, and others are almost complete. Mozart's genius is also to be found in these compositions, brilliant and captivating.

Each of these fragments and unfinished compositions, even the shortest, has its own particular background and story. Much more interesting than their history, however, is that which remains hidden in these works, their unfulfilled 'musical potential.' To conjecture about how Mozart might have continued or finished these compositions is a particularly entrancing pastime without end. The fragments and unfinished works for piano gathered on this recording contribute to a particularly personal and perpetually evolving image of Mozart insofar that one is continually confronted with the question: what might have been if ...

Mark Manion, adapted from Hiroshi Ishii

***

Duo Crommelynck

Duo Crommelynck has had an unparalleled career, and with their success they have brought a once forgotten phenomenon back into popularity: the piano duo and its extensive repertoire. Patrick Crommelynck studied with Stefan Askenase at the Brussels Conservatory, with Victor Metjanov at the Tchaikovsky Conservatory in Moscow and with Dieter Weber in Vienna. Taeko Kuwata studied with Kazuko Yasukawa at the Toho Academy in Tokyo and in Vienna with Bruno Seidlhofer and Dieter Weber, in whose class she met Patrick Crommelynck. In 1974 they joined forces to form a duo, embarking on a brilliant, international career. Their recordings have won numerous international awards.

The Duo Crommelynck's prodigious repertoire extends from the 18th century to contemporary compositions, some of which have been composed specifically for them. Included in their repertoire of over thirty programs are original works for piano duet as well as piano versions of major symphonic works.

Return to the album | Composer(s): Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart | Main Artist: Duo Crommelynck